|

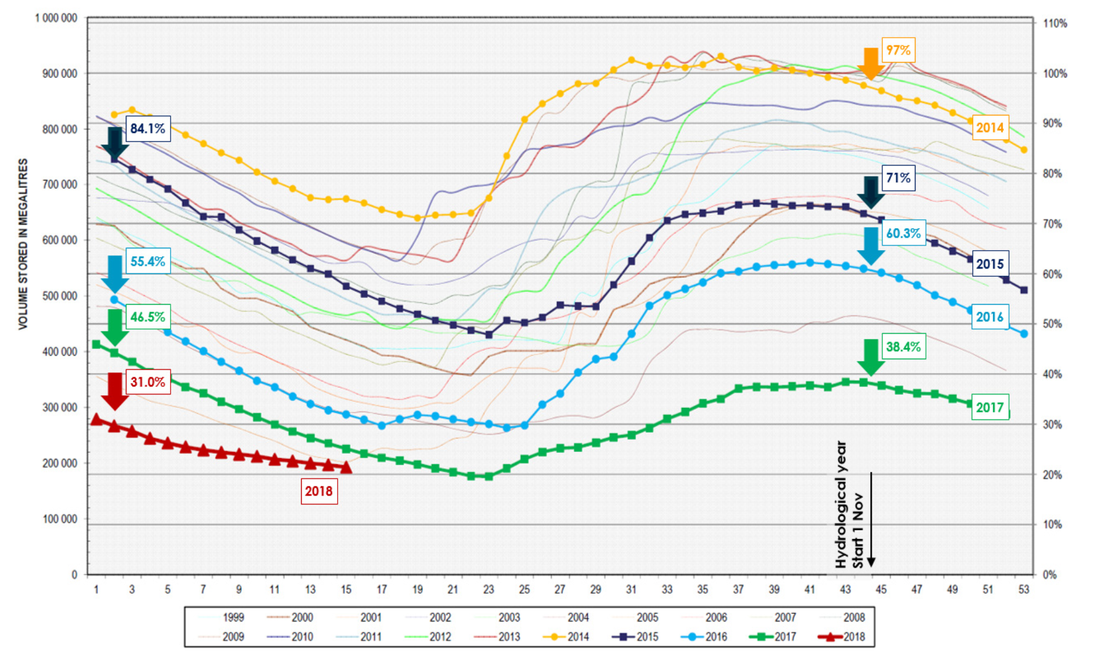

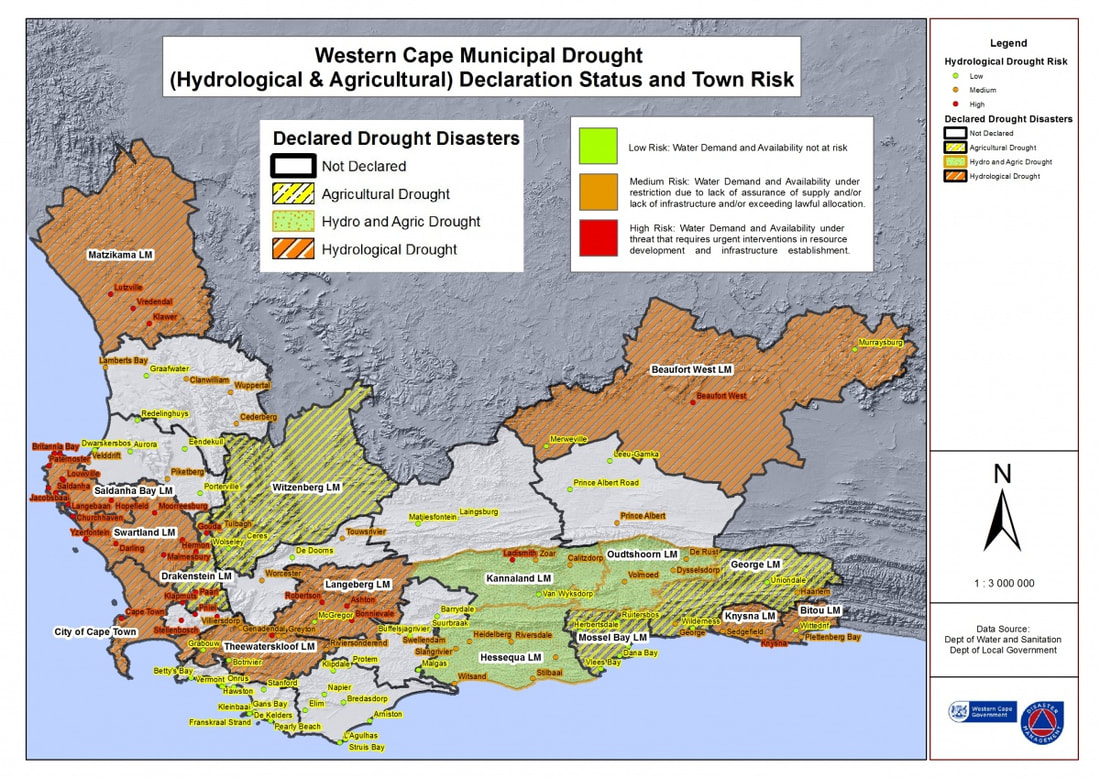

While the drought in the Cape Town area has been ongoing for several years, it wasn't until earlier this year that it became a global news story, in conjunction with predictions that the city's pipes would run dry around the middle of this year. While it's now thought that this dramatic situation will be (barely) avoided, at least in 2018, the mere specter of a moderately-wealthy city that shows up on every globe bumping up against a hard resource limit has jumpstarted many conversations about the seriousness with which the management of essential natural resources must be taken. In the 21st century, the developed world has generally speaking distanced itself far enough from needing to constantly assure the supply of critical requirements for life that it's jolting to be reminded that their constancy is the product of human engineering and innovation, rather than any immutable law of nature. Just as we now worry little about cholera in the water, we are extremely confident that there will be water in the first place, regardless of the fluctuations we see going on around us. In Cape Town's predicament -- a consequence of high natural variability in rainfall, warmer temperatures that evaporate more water, and the lack of a serious backup plan such as desalination or larger reservoirs -- is a vivid reminder that sometimes you get dealt multiple poor hands in a row. The only upside of such a "Day Zero" is the action that it incentivizes, and the rethinking of previously unquestioned norms and assumptions.  Total water volume stored in the reservoirs that supply Cape Town, showing the seasonal and interannual variations as well as the steady drop from the wet year of 2014 to the dry years of 2017 and 2018. The slower drop in water levels so far this year is due to restrictions placed on both urban and agricultural water users. Source: "Water Outlook 2018" report at https://coct.co/water-dashboard/ The Cape Town situation is a complex stew of factors, ranging from inequality between the poor and the wealthy, between native Africans and white/Asian immigrant groups, and between agricultural and urban water users to poor planning, population growth, and sheer bad luck. It took many or all of these for the current situation to develop; after all, this is only one instance in multiple decades, and one city out of hundreds or thousands of its peers. However, in these overlapping, interacting, and sometimes self-reinforcing aspects it serves as a premonition of the kinds of tensions that could occur around the world in the future over shifting availability and constancy of resources. California, for instance, is expected to see stronger seasonal and interannual "whiplash" between wet and dry conditions, making an already-challenging water-management task that much harder. I would argue that climatic change is a bit like economic change in that way -- not in the sense that it's inherently good or bad, but that the most-consequential changes involve the way that they disproportionately benefit certain groups or places while harming others. To take a non-extreme example, comfortable (dry and mild) weather is expected to shift poleward over the coming century, with sharp decreases in such days over developing countries in the Americas, Africa, and South Asia contrasting with increases in Canada, northern Europe, and various sparsely populated highland regions. Despite the grand burden-sharing promises of e.g. the Paris climate accord, it remains a very open question as to whether there'll be any mechanism in place to prevent these benefits from flowing directly to the already wealthy and leaving the global poor in the lurch, suffering from a problem they didn't create in the first place. From a decadal-climate-change kind of perspective, these localized Day Zeros may serve as a blessing in disguise if they force the underlying problems (which are global in nature) to be reckoned with before the impacts grow to truly uncontrollable sizes. As the map below shows, the Cape Town drought is remarkably concentrated in the city, its immediate suburbs, and the nearby mountains where its reservoirs are located; a drive of just an hour or two reaches unaffected areas. This makes the problem, while of course quite severe in its local impacts, qualitatively different than say large-scale water stress due to glacial melting and the loss of their summer-storage capabilities. One can imagine a slew of other Day Zeros, ranging from the first locations to hit unsurvivable wet-bulb temperatures to the advance of "warm-weather" insect pests into boreal forests. Due to their concentration of people, assets, transportation links, and media outlets, many of these impacts will be felt first in cities, or at least reported on there. This makes knowledge of when an urban area's Day Zero might occur, and how to prepare for the case that it does, of great importance for keeping global society within comfortable bounds that allow basic requirements to always be met -- as we've come to mundanely expect, without giving much thought as to what it takes to ensure this. Between still-growing resource demands, ever-present natural variability, and the shifts in both means and standard deviations due to anthropogenic climate effects, those kinds of unquestioning assumptions bear some significant revisiting.  Drought status as of Aug 2017 for municipalities in the Western Cape region. While Cape Town and its immediate neighbors were and continue to be in severe hydro-agricultural drought, other areas within 100 km of the city have secure water supplies. Source: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/text/2017/August/western_cape_drought_map_risk_and_declared.jpg

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed