|

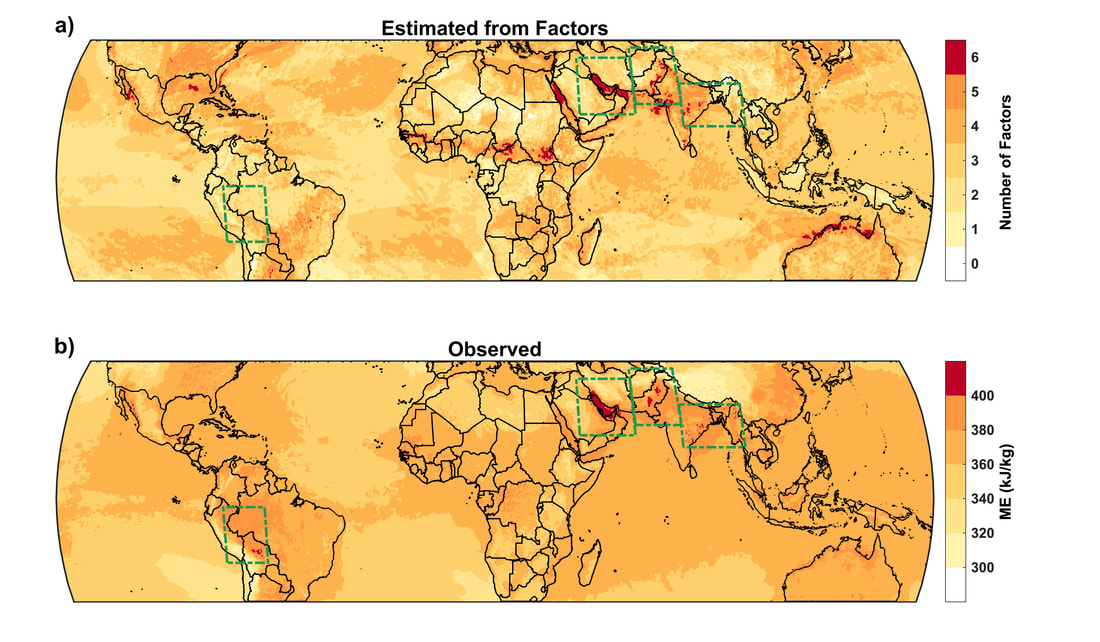

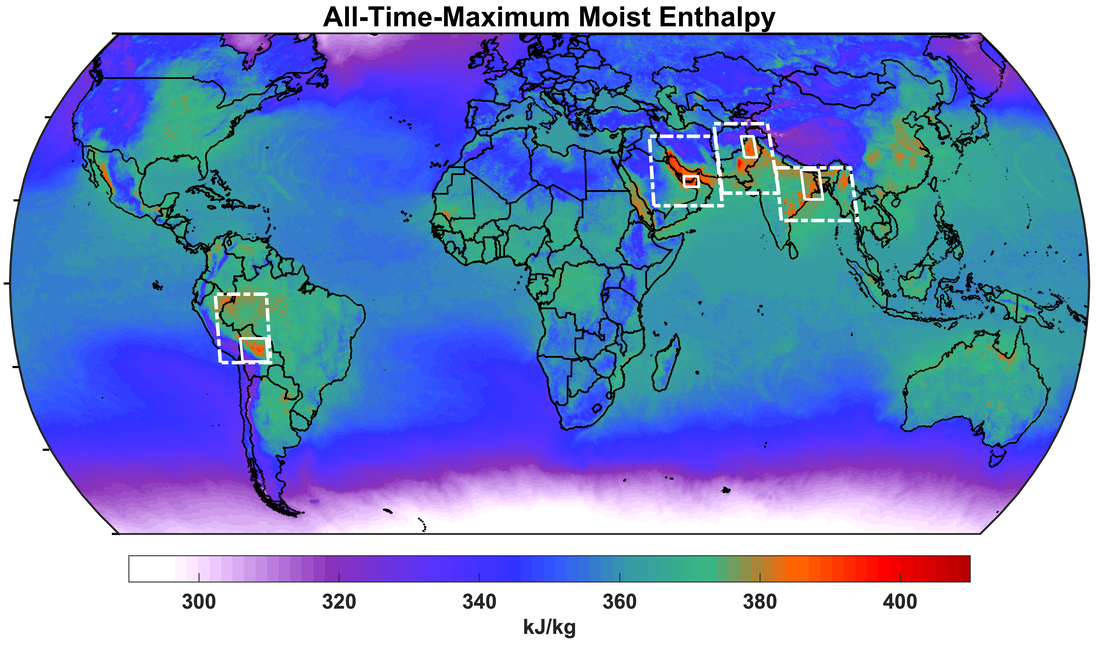

An explosion of research in the last decade has explored diverse aspects of climate-system extremes, from theoretical, observational, and model-evaluation-based standpoints. We now know much more about the parameter space in which the planet operates, and how anthropogenic climate change is tugging at its boundaries. But there remain some grade-school-type questions about extremes where our understanding is surprisingly vague. For example, the single best-observed variable that we have is arguably near-surface air temperature -- and yet, how to explain why are its highest values in Mesopotamia, Pakistan, and the Mojave Desert, rather than in the Sahara or Australia? These questions quickly veer from the academic (few people live in forbidding deserts, after all) to the critical when considering heat stress, precipitation, wind speed, or any other of the myriad variables whose most intense extremes may occur in populated regions and which therefore have the potential to seriously affect lives and livelihoods. In our recent paper in GRL, we try to build on what is already known about heat stress (i.e. humid heat, which we consider as simply temperature + humidity) to build a first empirical hypothesis about the processes which control it. The paper's genesis came when we noticed that humid heat very close to the global maximum occurs in regions with quite different climates: Pakistan, the Persian Gulf basin, parts of the Amazon, eastern India, and coastal Mexico, among others. These are both coastal and continental; tropical and subtropical; monsoonal and desert. We wouldn't be climate scientists if we didn't start immediately wondering about their commonalities, and in particular, why other places (like coastal North Africa, Southeast Asia, or northern Argentina) have distinctly lower maximum heat stress. Clearly from the figure below there are some latitudinal effects, a relationship with summer temperature and aridity, a relationship with marine moisture, a relationship with monsoon circulations; but how do these all play out and explain the observations for a particular region? Our initial ambition was a complete spatial (latitude+longitude+vertical) and temporal picture of heat and moisture states and fluxes in a variety of regions. Such a scope quickly proved impractical, so we settled on a more selective analysis of four regions (white boxes in figure above), which still encompass a diversity of meteorological and geographical factors. While the regions differ in many respects, two key characteristics ultimately emerged: places and times with globally extreme humid heat have abundant low-level moisture and no deep convection. Even slightly cooler sea-surface temperatures or slightly greater atmospheric instability were associated with substantially lower peak humid heat, which in previous work we've shown can occur for just a few hours before dropping to more manageable (but still oppressive) levels. We then leveraged these crude but robust correlations to predict locations of globally extreme humid heat using circulation, radiation, and flux proxies and cheating a bit by designing criteria to exclude certain climate regimes such as tropical rainforests. Nonetheless, our criteria include no information about the actual near-surface temperature or moisture patterns. Our predicted patterns match the observed ones fairly well (see figure below), particularly notable for the two regions with the highest humid heat -- South Asia and the Persian Gulf basin -- whose contrasting climates lead to quite different ways of achieving the high-moisture/no-convection combination. [This is explored in the paper.] The general idea of other regional maxima also agrees, such as northwest Mexico and northern coastal Australia. There are of course a number of places where the simple model gives under- or overestimates, including the western Amazon, central Africa, and northern Red Sea, and it generally underplays the risk of extreme humid heat over oceans. But the standards for success are always lower when there is a lack of direct precedent.  Empirical factors determining the geography of extreme humid heat. (a) Number of hypothesized important factors present at each grid cell, assessed via criteria involving nearby warm SSTs or large latent-heat fluxes; downward motion; exclusion of areas with extreme shortwave radiation; high but not extreme net longwave radiation; moderate annual-median relative humidity; and elevation <500 m. (b) Observed all-time humid-heat maximum (as measured by moist enthalpy). The complexity of Earth-system science, especially now that it is converging with other fields in recognition of our managed-planet reality, means that studies are often like forays into a cave with a lantern: they can raise an order of magnitude more questions than they answer. From our work, some of the most interesting would involve peeling back the onion skin another layer to discover, for example, precisely how topography aids in producing a stable shallow boundary layer in some regions and at some times (but not others), and the time-varying proportion of water vapor originating from marine versus continental sources (and its sensitivity to various atmospheric and marine perturbations). The former would help pinpoint climatological humid-heat hotspots, particularly in data-sparse areas with complex terrain; these hotspots are especially relevant as climate change lurches us closer to the 35C physiological survivability limit for sustained exposure. The latter would help determine how we might manage agriculture, urban, and energy systems to mitigate humid-heat extremes even incrementally, such as by limiting irrigation for critical several-day periods due to unfavorable synoptic conditions.

We hope the simplicity and generalized nature of our conclusions makes them useful as a basis for further work to closely examine processes in certain regions and at certain timescales; to consider the effects of mitigation or adaptation measures; or to understand time-dependent relationships with precipitation. Implementing a rigorous causal framework and using it as a constraint on data-driven machine learning would neatly expand on our work while retaining a level of parsimony and interpretability. Regrettably, humid heat will doubtless weigh more and more on people's minds, and their wallets, as climate change progresses. Marshalling a compendium of local and regional studies, that consider physical processes and their human-systems feedbacks across scales, is probably the single most effective tool for motivating meaningful individual and collective action; however, the flow of motivation can go both ways, as a coherent global framework can also prove invaluable for simplifying and linking research in ways that appeal to 'big-picture' thinking. Facing such a crucial and long-term global issue, all of these zoom levels must be pressed into service.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed