|

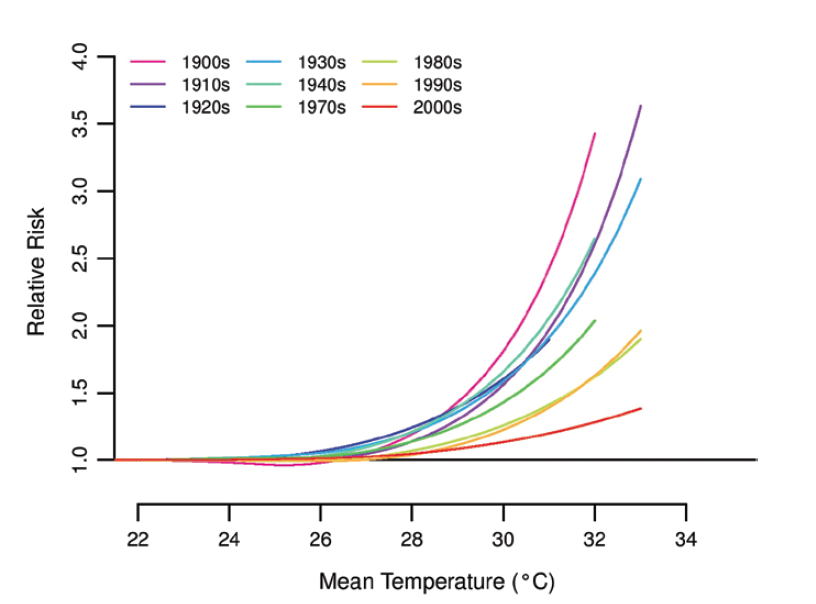

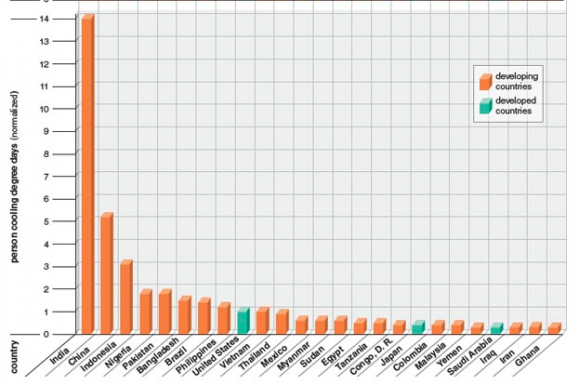

I went to a cool talk recently, titled COOL, that featured Stan Cox, a geographer interested in the cultural & environmental context & effects of A/C usage. He noted, astutely, that "the middle of a heat wave is the worst time to talk rationally about this". Within the US and other industrialized nations, A/C has become nearly universal except in the coldest regions, and in fact much of our lives are predicated on the existence of it in nearly unlimited quantities, so that it's hard to imagine doing without it. For instance, the Sun Belt commuter who in the summer moves between air-conditioned buildings in an air-conditioned vehicle, a daily routine that exposed to the heat of the untreated air would be intolerable. Also, many new high-rise buildings are built without even the capability for natural ventilation on the scale that would be needed, on the presumption that it never will. The huge role of A/C in economic development, particularly of the American South, led the history professor Raymond Arsenault to quip, "General Electric has proved a more devastating invader than General Sherman." The below figure shows the dramatic decrease in heat-related mortality in NYC over the decades of the 20th century, beginning in earnest in mid-century -- coincident not just with the advent of widespread A/C, but also with the universality of electricity (and thus fans, refrigerators, and reliably cold water); with greater numbers of sidewalk trees; and with reductions in cardiovascular disease, a major risk factor for heat-related mortality. [The figure is based on epidemiological work suggesting that publicized numbers of heat-related mortality are underestimates because they mostly represent heatstroke and not the more-common case of heat strain exacerbating underlying health problems.] To do a back-of-the-envelope calculation, a city of 8 million and a life expectancy of 75 years (i.e. NYC in 2005) should average 290 deaths per day; a city of 4 million and a life expectancy of 55 years (i.e. NYC in 1905) should average 200 deaths per day. Combined with an annual maximum daily-average temperature around 31 C, these curves mean total deaths on the hottest day alone fell from 500 in 1905 to 350 in 2005, and excess (heat-related) deaths fell from 300 to 60. Conservatively, anti-heat technology (broadly speaking) has saved hundreds of lives per year just in NYC relative to a century ago.  Curves estimating the total number of deaths in New York City for different hot temperatures over the past 110 years. For example, in the 1940s the city would experience roughly twice as many deaths as normal on a day with a mean temperature of 31 C. In a city of 7 million people, this translates to 550 deaths vs. 275 normally, or a daily heat-related death toll of 275. Source: Petkova et al. 2014. However, the talk also emphasized the more-deleterious effects of air conditioning, both well-known and less-known: energy consumption and resulting pollution (though on extremely hot days outdoor ozone is more of an issue), and freon that contributed for many years to the creation of the 'ozone hole'. Then there are social effects: for one thing, A/C may encourage social isolation, and for another, people who work outside or in factories have not benefited during their workday from the universalization of indoor A/C, but nonetheless experience hotter temperatures due to the waste heat from A/C units and the greenhouse gases to whose emission they contribute -- a bit like the Pacific Islanders who have contributed least to global emissions but have the most to lose from sea-level rise. Maybe, as the moderator of the Q&A discussion suggested somewhat fancifully, outdoor workers can someday have "little air-conditioned bubbles" akin to how clothes are a efficient personal 'warming bubble' in winter. [Update, 9/6/16: with new cooling fabrics, this idea is perhaps not too far away after all!]. This issue is of concern not just out of fairness, but because many of these outdoor workers are essential but invisible cogs in the modern urban postindustrial economy: they are construction workers, delivery personnel, etc. The COOL talk was held on a hot and humid day, and while bicycling home I began paying more attention than before to the significant number of deliverypeople on bicycles, for whom the heat was not a 15-min blast as for me, but a grinding background presence to their hours-long shift. Ironically, many of them were making deliveries for companies (e.g. organic food & restaurant companies) that bill themselves as not only convenient but environmentally friendly and socially just -- yet upon closer inspection these claims begin to waver, like heat mirages. On the other hand, A/C can aid in reducing inequality as well; despite the efforts of "open-air crusaders" in the '20s, schools (at least in the North) have been some of the last buildings to have A/C of any kind installed -- 25% in NYC still lack it, often because of inadequate electrical systems. Uncomfortably high temperatures have a clear effect on academic performance, and it is not a stretch to imagine how this sort of 5% or 10% disadvantage can add up over time to affect students' career trajectories, in a world where the difference between acceptance and rejection is often just several percent. As with many advances in efficiency or capacity, A/C's decreasing cost has led to perverse increases in usage, often to the point of wastage -- as, Mr. Cox pointed out, any office worker who's worn a sweater in August is well aware. Combined with figures like the increasing number of square feet of building space per person, it's no wonder that power used to run A/C jumped 37% between 1993 and 2005, even as efficiency increased 28% . The perception of limitless supply of something is often problematic (e.g. suburban sprawl), and in the case of A/C this effect is enhanced by the stubbornness of prestige surrounding the ostentatious use of A/C, as a reporter for the New York Times discovered in 2005, summarizing a round of department-store tours by noting, "The higher the prices, the lower the temperatures." Perhaps this prestige factor is to some degree behind the freezing-office phenomenon as well. Besides ostentation, dependence on A/C (like designing buildings to not allow for natural ventilation even on reasonably temperate days) and ignorance of the electrical demand it produces can combine to lead to a backfiring effect when systems get overloaded and shut down, as in Chicago in the 1995 heat wave, when high demand led to outages and thus for a while in certain neighborhoods no one had any A/C at all. Mr. Cox argued that a large but unspecified fraction of A/C usage is 'nonessential', i.e. primarily for comfort rather than health, and thus could be made unnecessary with thoughtfully designed buildings, cultural shifts, conscious efforts at acclimatization, etc. In New York City, anyway, I found this to be true: in the past 20-odd years, there have been an average of 1094 hours with temperatures in the 75-85 F range, against just 168 hours with temperatures 86 F or higher. Emissions in both New York City and the United States as a whole have fallen since their peak around 2005, but in terms of going further A/C certainly seems a low-hanging fruit. Looming over any discussion of the excessive use of something by the U.S. (and there could be many) is the logical desire for aspiring, developing countries to use that thing at the same per capita rate, and the enormous environmental cost that would be borne if that came to pass. And unlike for electricity or water in general, which are in relatively constant demand no matter the climate, A/C is most used where it's hot -- and the poor of today are overwhelmingly concentrated in the tropics. In James McNiven's book "The Yankee Road", former Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew of Singapore lauded A/C as making his country's rapid ascent to and maintenance of a high standard of living possible, both in increasing productivity and in making the city desirable to expatriates. Temperature does have a real effect on productivity -- Burke et al. 2015 found an annual average temperature of 13 C maximized productivity across the world and across economic sectors -- probably not coincidentally, this is almost exactly the climate of New York City (12.8 C) and London (12.4 C). Mr. McNiven also notes that without A/C, technological and industrial centers like Bangalore and southern China simply would not be possible. But Mr. Cox estimates that if tropical populations were today using A/C at the same rate as the US, global power dedicated to A/C (currently 10% of the total) would increase tenfold -- larger than that for all other usages combined as of today. A/C also has a negative effect on physiological acclimatization to heat, contributing to a cycle of more and more demand driven by physiology in addition to the cycle driven by waste heat and greenhouse-gas emissions.

So A/C is almost like a riddle: essential but superfluous, a luxury and a necessity, a solution and a problem. With all the above considerations in mind, it will have to be part of a larger set of approaches to optimally negotiating the often-testy, always-complicated relationship between humans and the environment.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed