|

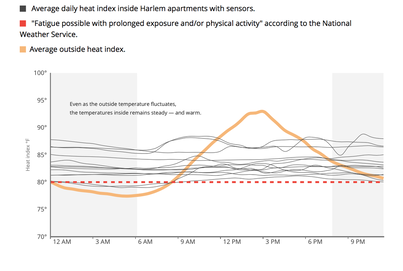

Last week I attended a panel on extreme heat, which like many recent events had the seemingly mandatory mix of representatives from the four corners of science/applied science -- government, nonprofit, business, and academia. While this attempt at interdisciplinarity is often more like the sound of many voices speaking rather than a choir singing, it does reveal certain aspects of scientific problems that have not traditionally been appreciated, and suggest certain solutions to them. The large attendance that these events often attract is a testament to this value in this regard. Heat has long been a serious but underestimated threat. Multiple stories on the topic are included in WNYC's "Harlem Heat Project", among other notable public-facing science efforts. Heat is not like tornadoes or hurricanes, which come in with obvious force and create indelible images of destruction; it's a silent killer, striking people in their homes, often in cities, almost occurring right under the noses of doctors, researchers, and civic organizations. Vulnerability to extreme heat has dropped significantly over the past century, with the spread of electricity and (most importantly) air conditioning, but it remains the single biggest source of weather-related mortality in the US -- in NYC, it averages about 100 deaths per year according to the city health department. The panelists agreed that to a certain extent this is the result of a messaging problem: warnings about heat often are illustrated with people exercising or working outdoors, while in fact the majority of heat-related deaths occur indoors, to sedentary people already in poor health. Cities are a danger zone for extreme heat, particularly looking toward the future. Outdoor temperatures in cities are hotter than elsewhere by up to 10 F due to the urban heat island, and urban residents tend to spend significant time exposed to these conditions, whether working, commuting, or doing errands. On top of this, poor airflow in cramped spaces of the urban landscape results in pockets of heat that can be severe. For example, underground subway station platforms in New York City are stiflingly hot in the summer. Small apartments, in buildings packed close together, heat up at the beginning of a heat wave and don't cool down (day or night) until it's over (see figure below). With such conditions, it's fun to imagine powerful but unorthodox solutions, such as agriculturally inspired 'heat fans' on the Hudson to help alleviate heat trapped in the canyons of Midtown. In contrast, current attempts to remedy the issue are generally incremental and woefully inadequate, and (by the city's own admission) usually do not reflect 'best practices'. For instance, the advertised network of official cooling centers consists of voluntarily offered spaces whose availability fluctuates from season to season, are non-uniformly distributed, and are unattractive for spending significant amounts of time. Needless to say, this putative resource is heavily underutilized. Part of the problem is societal and universal -- the desire to 'hunker down', even in the face of an imminent, obvious, and instinctual threat like a hurricane. Thus, a significant fraction of people don't want to spend money on something they consider a luxury rather than a necessity. There is also the age-old trope that issues affecting the poor or otherwise disenfranchised attract less attention and funding, from the private and public sectors alike.

Looking forward, proposals the panelists mentioned included policy solutions (e.g. mandating cooling rooms in all new buildings), technological solutions (e.g. health-monitoring devices), and social solutions (e.g. encouraging cohesion among building residents). Improving messaging about who heat's victims really are could make a big dent in the problem also. Much of the implementation challenge is governance: city agencies don't coordinate their efforts, resulting in a struggle to get funding even for projects that would save money in multiple ways (e.g. reducing subway heat would also reduce taxpayer-funded medical treatment for heat exhaustion); and city, state, and federal governments often work at cross-purposes, or with incomplete information. As global-mean warming continues, baselines are shifting so rapidly that (as one panelist said) we almost expect extremes now, at least as defined relative to the 30-year retrospective temperature distribution. Together with increasing knowledge of the wide-ranging impacts of climate extremes, and how these impacts cascade through many realms of society, this motivates calls for what could be called a 'new environmental ethics' -- that is, broad awareness of the causes and externalities associated with extreme heat and pushes for creative ways of solving them. For example, one such solution could involve discounts for reducing personal vulnerability, much like health insurers already give discounts for gym memberships and other healthy activities. A carbon tax on energy producers is another clear candidate. With these kinds of market failures properly addressed, it would not be long before more creative approaches come along in the urban planning, public health, communications, and policy realms, spurred on by the incentive to improve lives and make our societies more resilient to extreme heat overall.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed