|

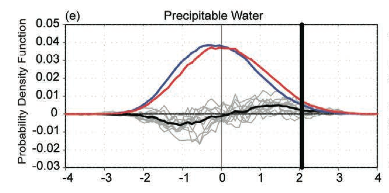

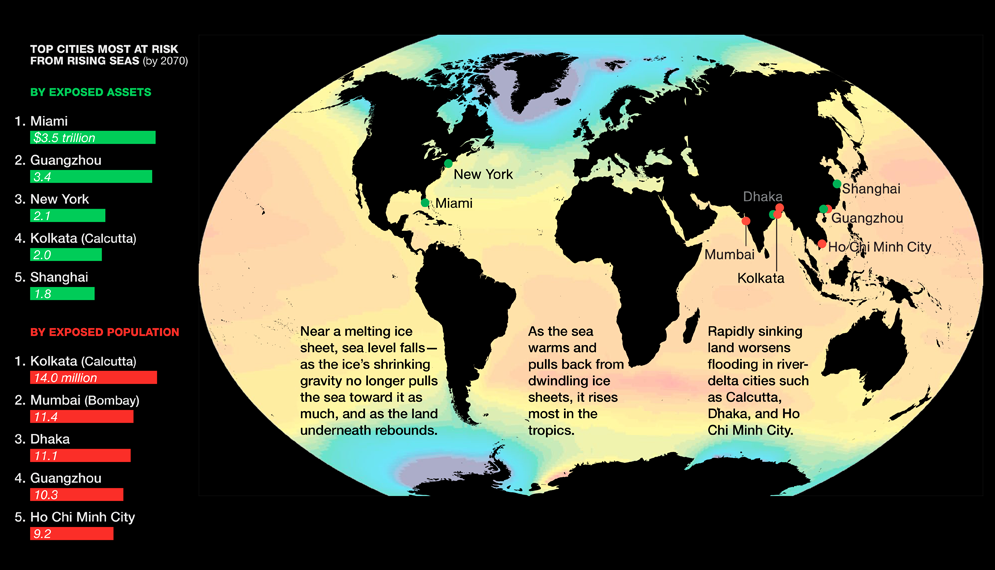

No matter what emissions scenario the 21st-century world ends up following, no matter what climate sensitivity turns out to be most accurate, no matter what geoengineering projects might be taken up, there will inevitably be places that experience huge disruptions as a result of climate change. This is not a radical statement, but one drawn on shifting probability distributions: even a marginal increase in the chance of some environmental *thing* happening due to increased greenhouse-gas concentrations implies an (equally marginal) anthropogenic fingerprint. Once the environmental part is attributed in this way, a whole slew of cascading effects can be as well. Of course, for some things (sea-level rise) it's a lot easier to say whether or not they would have occurred had we all stayed peasant farmers — or if we'd somehow skipped the coal-and-oil phase of industrialization and gone straight to renewable energy — than it is for others (specific extreme events). A thoughtful article comparing these definitions and reflecting on the challenges the whole interconnected system poses is here.  A sample of the challenge in attributing extreme events, in this case the recent California drought: The probability density function of water vapor over the northeast Pacific in the 1871-1970 period (blue) and 1971-2013 (red). The black bar marks the combined 97.5th percentile. Source: Herring et al. 2014. Disruption requires coping. Almost all coping strategies (conventionally divided into adaptation and mitigation) are predicated on the notion that incremental modifications in barriers, policies, building codes, technology, etc. will be sufficient to maintain society-wide quality of life at the same level and, crucially, in the same places. Conceding anything to Nature, even strategically, is a mark of weakness. In a way, this is a continuation of the view since time immemorial of humans as underdogs against an enormous and unforgiving natural world that must always be beaten back — a view that arguably needs adjustment given our modern technological arsenal and general omnipresence. (I recently read Bill Gail's "Climate Conundrums" which does a nice job exploring this perspective.) To be sure, the incremental-adjustment paradigm will be reasonable in most cities, with major impacts restricted to low-lying neighborhoods and certain regions. The changes must also be placed in the context of the long-term history of cities, which as expressions of their volatile creators are never finished becoming, But take off the big-picture glasses that pleasantly smooth everything out, and there are most certainly areas that despite all reasonable efforts and expenses will suffer greatly, if not become completely uninhabitable. Coastal Alaska is one such place, due to the combined effects of increased erosion and rising seas. Even small villages have relocation costs in the millions, and so it's hard to imagine the untold sums associated with "only" parts of a city like Miami being reclaimed by the ocean (the below figure giving a taste for the numbers). It's a bit of a cruel twist on the term 'underwater mortgage.' In the past, abandoned places have ranged from the Sahara Desert (as it transitioned from grassland) to Pripyat after the Chernobyl disaster, as I mentioned on the Background & Stats page. Astute readers will have noted that in the litany of adaptation issues proffered by the IPCC, the very first under 'Infrastructure/settlement' is relocation. This is an interesting choice — perhaps intended as a political statement of seriousness — instead of emphasizing, say, seawalls, water pipelines, and air conditioning. Whether 'climate-induced migrants' eventually number in the thousands or the millions, and whether they are moving between neighborhoods or between countries, the question of what precedent to set is an important one that will be a subject of negotiation at the Paris climate talks next month. Beyond normal humanitarian aid, a reasonable approach would be to make assistance for those most affected proportional to the probability (using historical-climate simulations) that the aspects of the event that caused the suffering were attributable to greenhouse-gas emissions, and then break the assistance down further by countries' integrated historical contribution to current CO2 levels. All a pipe dream of fairness, probably, but one can hope. Finally, entertaining the notion of city relocation brings up for debate questions about regulation vs. individual freedom — literally, in the case of building along low shorelines, about sunk costs. Should society (through disaster relief, insurance subsidization, etc.) be encouraging and enabling continued investments in vulnerable places? How vulnerable is too vulnerable? Non-sea-level-related changes (like extreme heat and water shortages), while certainly formidable, will probably prove easier to address in situ than relocating millions of people. In many cases, ameliorative technologies new (desalination plants) and old (traditional Arabic city design) are available and simply need to be effectively scaled up, and as demand rises costs will continue to fall.

When it comes to our interactions with the environment, the 'fight or flight' instinct is just as applicable on a global environmental scale as it is when facing a threatening animal. A judicious mix of them will have to be employed, and flight occasionally resorted to, although the fighting will no doubt comprise the vast majority of our adaptation efforts. If nothing else, our stubbornness in insisting on continually living life in parts of Earth where conditions are poorly suited for it will be good practice for when we begin colonizing other planets.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed