|

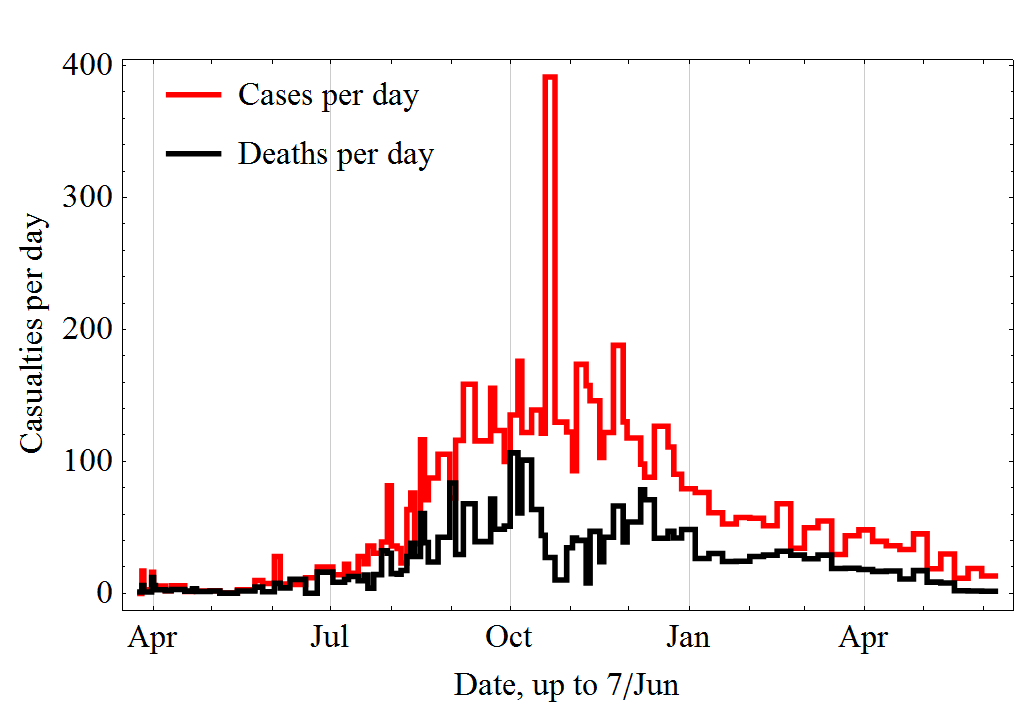

Just about everyone professes to love media these days, and particularly its 'power'. But power can be destructive as well as constructive. The big question then is (at least for the purposes of this blog), does (mass-)media attention skew public perception of weather and climate, and of trends therein? Public opinion is important for its influence on policies from the international to local scales, and insofar as the quality of an opinion is proportional to the knowledge from whence it derives, public understanding matters too. A competent and engaged citizenry can particularly effect impacts in urban areas, whether the engagement is political, physical, or moral. In addition, broadly accessible, accurate climate knowledge is desirable from a philosophical standpoint, and a big part of determining that is the faithfulness with which scientific findings are filtered and transmitted onward to a wider audience. It's human nature, and consequently the nature of our media, to bring an issue sharply into focus for a while and then to have it recede into the distance of our collective consciousness. Events perceived as sufficiently worthy — because they are dramatic, heart-wrenching, concerning, etc. — draw our eyeballs and ears, then our hearts, and in some cases our time and pocketbooks. Then, barring new developments, some successor appears and displaces them. This sequence means that the public measure of a thing tends to rise and fall in exaggerated proportion to the oscillations of its 'true' measure — whether that thing is the price of a company's stock, the concern about a disease's impact (see figures below), or the state of the Earth's climate. There is considerable evidence that, when it comes to environmental issues, the intensity of media attention often does not match the deservedness of the story, but rather is determined by the political relationship between the country of the writers and the country being written about; the amount of drama that the issue presents; the wealth, race, etc. of the people affected; and so on. Although this general pattern is known from intuition, the degree of it is rather shocking: the death toll of a disaster in Africa must be 40 times that of one in eastern Europe to achieve the same level of worldwide coverage; multiply that factor by 1,000 and that's how much more the media focuses on fatalities from volcanoes versus droughts. That article also discusses how the prominence of stories rises and falls as the 'news cycle' goes around and as more-immediate issues crop up — for example, the percentage of Americans saying 'global warming is not happening' doubled from 2008 to 2010 as the economy fell into recession (compounded by "Climategate" in 2009). To the extent that the majority of the public's understanding of climate issues is framed by media coverage, there is significant potential for distortion relative to the scientific understanding. Films like the recent "Merchants of Doubt" are predicated on the assumption that people's grasp of the issues is indeed muddled by media portrayals (as opposed to, for example, representations of uncertainties about anthropogenic climate change and undue certainties about short-term forecasts merely reflecting independent public appraisals). There are also simply unintended consequences in perceived relevance of a topic when fluctuations in attention to it vary by an order of magnitude. A study analyzing word choice in articles about climate in U.S. and Spanish newspapers found the overall characterization of a weaker scientific consensus in the U.S. as opposed to Spain, matching public-opinion differentials, and further that over the 2001-07 period U.S. writers highlighted 'change' and 'surprise' with greater frequency (regardless of ideological bent) even as the scientific backing became more solid. It may be argued that this resulted from a desire to better characterize uncertainty, which is generally poorly understood; in any case, it was associated with a shift in U.S. public opinion in the opposite direction from that of scientists. Responsibility also partly rests with the scientists, of course, who as a group have not excelled in communicating to the public the complexities of their fields largely without the aid of explanatory figures and Q&A sessions that are the bread and butter of scientific conferences. A similar study in Malaysia published last month noted cyclical trends in climate coverage in local newspapers, in accordance with what is termed 'agenda-setting theory' — that media serve not just as actors in a broad societal pageant, but as directors who shape its contours. It's a tough job, as there are complicated and interlocking series of trade-offs: for example, focusing on anthropogenic impacts on the environment stimulates feelings of salience but paralyzes feelings of capability to address them. One of the main resulting discourses has been somewhat of a distraction: namely, who has the proper authority to speak as an expert. There is also substantial evidence from other fields that the balance of public opinion is swayed by media coverage independent of the true nature of the topic — partly a reflection of 'availability bias' (whatever has been heard the most becomes the dominant impression). Further contributing to confusion has been the recent apparent increase in media attributions of extreme weather to climate change that are only partially even possible — and qualifying this with remarks about its being 'unsophisticated', while well-intended, does not seem likely to materially affect the overall impression of a definite causation pathway in the mind of the layperson. A recent review article focusing on North America considered this sort of lack of nuance concerning, arguing that the urge to simplify paradoxically often leads to greater confusion, as many people consequently (and again this partly goes back to tenuous grasps of probability distributions as well as the power of visuals) fall under the impression that every local event is 100% attributable to climate change. This is true for long-term trends as well: an article in Climatic Change noted that two of the main complaints about climate change in Switzerland (low-snow winters and cloudy summers) are not actually supported by the data. Taken all together, this may help explain why media usage and environmental-problem action-taking are so weakly linked. Indeed, in some circumstances the media consciously work to define a framework characterized by a nationally motivated aversion to climate-change mitigation concomitant with an insistence on the existence of the problem so as to unify those who feel victimized, thereby using climate awareness merely as a means to another end — as in the case of India. Social media, in contrast to its mass counterpart, is more like personal experience in that it is less prone to being filtered through the subjective lens of 'worthiness'. In other words, in broadcasting the full range of reactions to a particular event, it is in a sense both more authentic and more biased. As discussed earlier, this sort of immediacy can be a positive as well as a detriment in terms of guiding public opinion toward the current numerical understanding of the climate, depending on the conditions at a particular place and time (especially those experienced by influential people). Local experiences are not to be underestimated when it comes to their power to shape opinion, at least temporarily. On the other hand, social media are prone to what has been termed 'siloization' or the 'echo-chamber effect'. I will write more on this in an upcoming post. As at very least an extension — and at most a fundamental constituent — of human culture, perhaps it is the prerogative of the media to engage in some amount of sensationalism in order to move public opinion and motivate public action to address the issues that seem most pressing, before they get 'out of hand'. Or, equally, to deem action undesirable. People in large part rely on the media of necessity as their source of information on many issues. Yet this all is an extraordinarily imperfect game for a multitude of reasons, including the natural focus on short-term risks, the various biases that determine what ends up receiving media focus, and the collective attention span of the public (which, it may be argued, is the driving force behind the pace of the news cycle in the first place). It may be that the system we have, and the discourse it engenders, is the best that may be reasonably hoped for given constraints like public scientific literacy and curiosity. An interesting question. At any rate, the pendulum of society-wide opinion is always swinging, and so reporting on the science with no agenda other than the aim for truth would hypothetically tend to move it back in line with scientific understanding. The only question is how much time that shift would require, assuming that it's even possible.

0 Comments

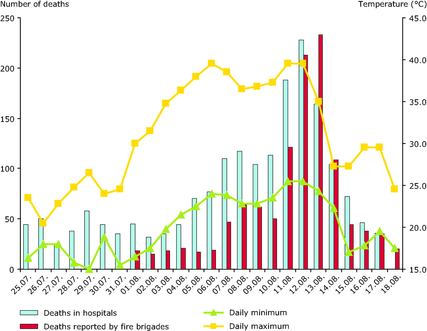

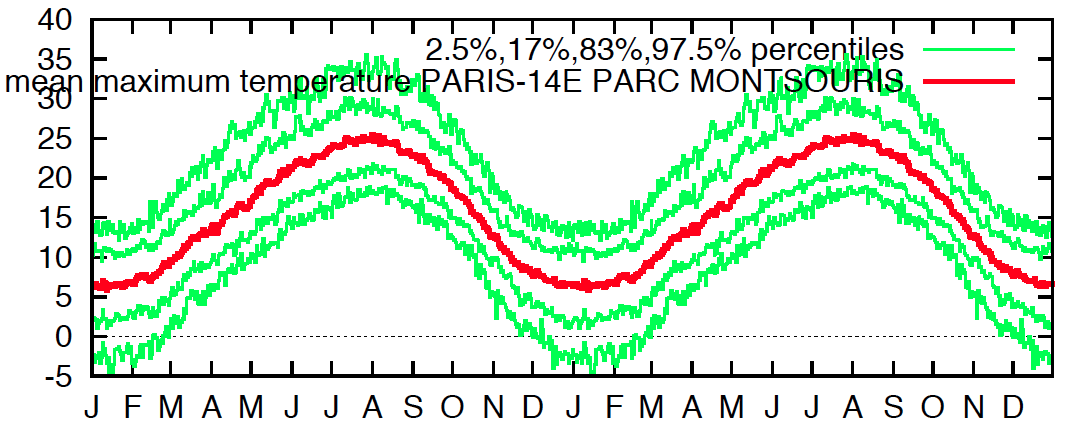

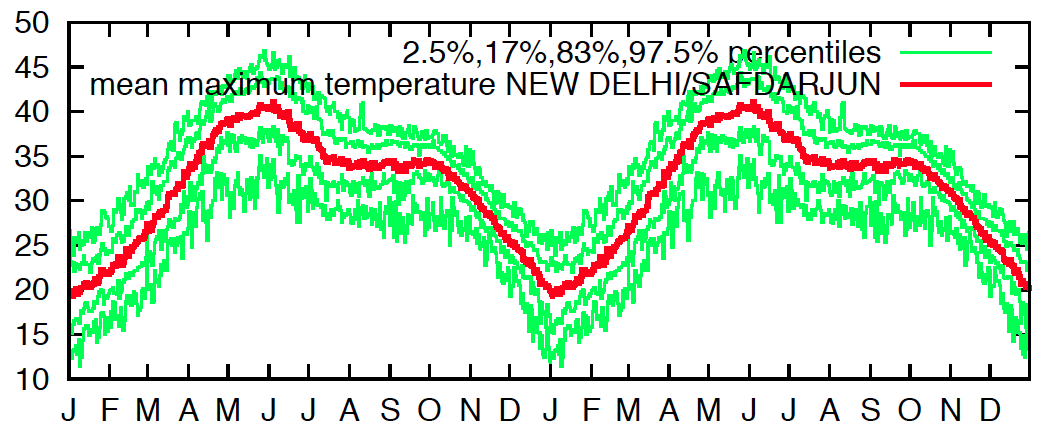

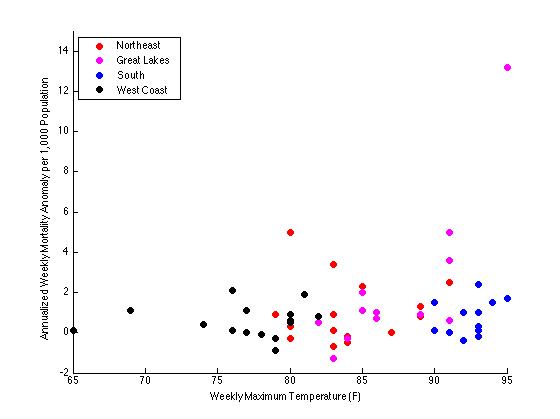

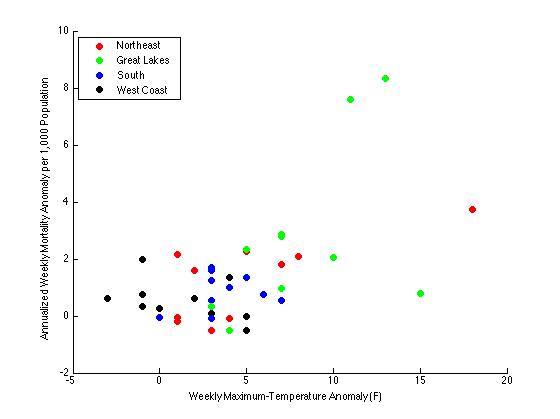

News of recent extreme heat in India ahead of the monsoon, and the associated mortality, brings up reminders of the gripping, society-wide impact such events can have. The term 'harvesting', used to describe long-term reductions in healthy lifespan from a severe event, is an appropriate one. The sheer intensity of the heat also prompts some consideration of the differences in impacts across regions; for instance, in 2003, temperatures in Europe were comparatively cool — peaking close to the early-summer average in New Delhi (see figures below) — and yet mortality was very high, even higher than in this May 2015 Indian heat wave where over a two=week period maximum temperatures averaged around 43 C (109 F) and minimum temperatures around 30 C (86 F). There are of course many differences between the two situations, but the difference in climatological baseline temperatures stands out. Is acclimatization of residents of warm climes a real phenomenon; is it strong enough to account fully for the difference in mortality; and does it imply that percentiles of temperature (i.e. values relative to the local climatology) are of sole importance for determining mortality? These are the multifaceted questions that this post will explore. When it comes to our environments, humans are amazingly adaptable — there's no doubt about that. This is true both on the individual and the species levels. Otherwise we could not have colonized nearly every climatic zone from the tropics to the poles; could not survive on exceedingly variable diets; could not live in city apartment towers when a few short generations ago most of our ancestors lived as peasant farmers on plots thousands of miles away. The only real question, then, concerns the length of the timescale of adaptation to a given perturbation. In biology, this discussion is often framed as a contrast between genetic and epigenetic components (e.g. for adaptation to high altitudes); but those are things that happen over generations or centuries. A study several years ago in Physiological Genomics specified heat acclimatization as "a reversible 'within-lifetime' phenotypic adaptation to long-term elevations in environmental temperature" [emphasis mine]. What can be considered 'long-term' with respect to extreme high temperatures (or any temperatures for that matter)? The answer has bearing on the comparative utility of absolute versus relative measures of temperature-related discomfort: if acclimatization requires a full season or longer to develop, then absolute readings make more sense, whereas shorter and shorter timescales mean relative ones become preferable. If it in fact takes years, the place of one's birth might confer a significant advantage or detriment. Uncertainty on this point is reflected in the National Weather Service's definitions of terms, where a heat wave is simply "uncomfortably hot and humid" but a heat advisory is issued at specific temperature thresholds independent of the location's climatology. What does the literature say? Several studies looking at this question have in fact determined that the 'exposure-response' curve for temperature and mortality does shift with the underlying climatology. One study in Europe found that the daily-temperature threshold above which deaths begin to significantly increase is 29 deg C in the Mediterranean region versus 23 deg C in northern areas. However, with a higher absolute tolerance comes a greater increase in deaths per degree C above the threshold — 3.1% vs. 1.8%. Similarly, in Alabama defining heat waves in terms of percentiles relative to the climatology yielded the best match with excess-mortality figures. Altogether, the relationship between high temperatures and mortality seems to be stronger in cooler regions — a 'heat-wave effect' of 6.8% higher non-accidental mortality during heat waves in the Northeast U.S., but only 1.8% in the South. (However, these numbers are not significantly different at the 95th percentile.) In fact, recognition of these climate-mediated differences goes back all the way to some of the earliest papers on the subject, such as a study published in Public Health Reports in 1938. Among noteworthy findings like a 70% increase in total mortality during and immediately following the peak of the record-setting July 1936 heat wave (also see here), and a greater incidence of mortality in cities than in rural areas, the author observed that excess mortality was higher in the North despite being cooler than the South, and therefore that it seemed to be associated primarily with the temperature anomaly rather than the absolute temperature. A quick plotting of the data tables from that paper helps in visualizing the basis for this conclusion (see below). Note that in a more careful analysis many corrections would be made that would most likely narrow the conditional spread, e.g. considering in a more-sophisticated way the delayed response of mortality to temperature; using percentiles rather than the numerical anomaly; correlating with a combination of the anomaly and the absolute value; etc. Of course it's not just acclimatization that could explain regional variations in the mortality response: societal and personal awareness translated into preventive measures (e.g. wearing loose clothing, not exercising in the heat of the day, managing household airflow) maps onto the differing availability of cooling technology. But the 1938 study, predating as it does the mass adoption of A/C, suggests that while A/C may have reduced overall heat-related mortality, its effect was not to increase vulnerability in cool climates relative to warm ones where its use is now more widespread. Not ruled out, though, are design features like the large porches and generally more-open, low-density patterns of settlement in the southern U.S. vis-à-vis the North (especially in the past). On the other hand, it has been reported that heat stroke is more prevalent in Arabia than in North America — but it is unclear to what extent this is affected by influxes of pilgrims during the Hajj. Finally, regarding the timescale of acclimatization, a number of studies have shown that mortality is highest in the first heat wave of the summer; evidence points to a combination of a lack of acclimatization in the population and to the deaths of the most susceptible inflating the early-season numbers. That same study notes a specific figure of several weeks — short enough to be consistent with a intra-season decline in sensitivity for a fixed population, but too long to be of great help to pilgrims to the sweltering deserts of Saudi Arabia. A breakdown of Hajj heat-related mortality by country of origin would be an interesting way to further examine this.

So, to resolve the initial motivating questions: acclimatization is real, and it is likely by itself to account for a significant fraction of the reduced mortality of residents of warm regions relative to cool ones when confronted with the same ambient temperatures. It is not clear if this is true throughout the temperature spectrum (e.g. in the subtropical deserts); at least one study has suggested there is a hard upper temperature limit on the body's ability to function. At the other extreme, although percentiles seem in general to be better predictors of excess mortality than absolute values, no one suffers from heat in Ireland (never mind the Arctic). In the climate literature, little work has been devoted to controlling for other societal and cultural factors influencing the population's exposure and physiological-adaptation capabilities. These have been implicated in many of the 2003 heat-wave deaths in France (such as sleeping on hot upper floors of houses), so they are nontrivial in understanding inter-regional differences. Acclimatization timescales are in some sense mirrored in the non-instantaneous nature of heat-related mortality — perhaps the most apt analogy (almost equivalence) is that of a disease, where immunity is nice but only if one survives to reap its benefits. Nature abhors a discontinuity, so ideally the body would take a week or so of adjustment time to a hot climate or vigorous exercise in the heat. In other words, in the context of a trip to India in May, three of these precautions apply to the climate as well as to the food. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed