|

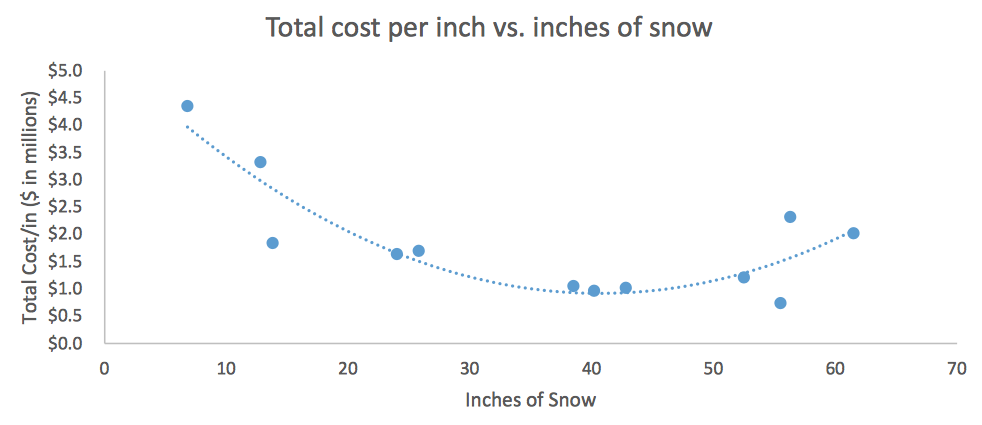

In a departure from some of the usual more research-laden posts, I will spend some time every once in a while examining topical issues revolving around the theme of city administrative and/or social adaptations to climate, and in particular to extreme climate events. Early July seems like the perfect time to delve into the first question I will look at: how cities deal with snow removal. Rather than being a complete non-sequitur, this was prompted most immediately by a recent article in the New York Times on the last garbage-filled hard-packed remnant of the enormous snow piles created in the wake of Boston's record-setting snowfall last winter. (Which set off the kind of repartee of dismissiveness often characteristic of the discourse between those two cities.) This mound's placement on the docks, but not actually in the water, caused it to reach 75 ft high (and made the mounding process difficult in the days following the storms) but kept the trash within safely out of the harbor. An article inspired by Boston's previous unusually snowy winter discussed several of the actions taken by other cities, including giant snow-melting machines, utilizing spare parking lots and old quarries, and perhaps the most desperate measure, emptying whatever was swept up by the plow's blade into the nearest waterway. Though expedient, given the visible dirtiness of urban snow even just a few hours after snowfall — plus the latent litter — this is hardly a desirable option from an environmental standpoint. From a cost one, though, it makes sense in certain cases, such as in locales with typically temperate winters. Where there is not much or any specialized snow-removal equipment, the closures necessitated have high costs. This means, depending on the forecast, simply waiting for the snow to melt (which can inspire strange conspiratorial hand-wringing when that doesn't work) is not always a sensible strategy — particularly when even the most-prepared of cities allows itself four or five days to fully remove 7" of new snow. And this with an annual budget of $145 million. Of course, even what's straightforward in principle becomes complicated once large numbers of people are thrown into the mix. Slow-moving trucks and improperly parked cars create obstacles to efficiency, while salt gets into waterways and onto floors. Expectations are high. This makes modern snow removal a complex operation, one that takes time to unfold. This time element makes the high snowfall rates of intense blizzards and lake-effect storms especially challenging; on the flip side, with preparation time being on the same order of magnitude as the storm length itself, by the time resources are mobilized and out patrolling the streets the forecast can have already changed — resulting in a general overestimation in years when eventual snow totals are low, as in the figure below. Coastal cities like New York tend to see large yearly snow totals due to big storms, rather than a series of light events, which pattern presumably explains the per-inch cost uptick for the snowiest winters. But snow removal presents challenges of a sort familiar to municipalities used to dealing with uncertain projections of population change, economic growth, political situations, and so on. Near-term weather forecasts are actually somewhat more accurate than economic ones (nicely analyzed in a reaction piece), though in large part this is because weather forecasters tend to hedge their bets much more than financial analysts do. Zooming out to a climate scale, the challenges of snow removal will tend to have less and less importance, as snow totals are expected to decrease in most cities around the globe, though with much regional variability due to storm-track shifts and the current winter temperatures in a region relative to 0 C. For example, northern Europe is expected to see more storms and higher wind speeds due to an intensified semipermanent low over Great Britain, but it is not yet clear whether the overall wintertime warming in that region will increase temperatures at the critical moments, i.e. the days immediately before and during intense storms, and consequently whether preparations for greater flooding or stronger snowstorms are more called-for in the British Isles and Scandinavia. In North America and possibly in Asia, mean snowfall is robustly expected to decrease, though with the caveat that localized areas (e.g. downwind of lakes) and events (i.e. the biggest storms) may depart significantly from this trend ["less common but more intense" is the phrase for what's often seen in models]. Taking a broader perspective, snow removal is a challenging aspect of municipal management in just a handful of major cities around the globe, and in generally wealthy ones at that, as seen in the neat time-lapse video from NASA's MODIS satellite below. And some cities would certainly be glad if snow removal were still the biggest thing their nations had to deploy the military against.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed