|

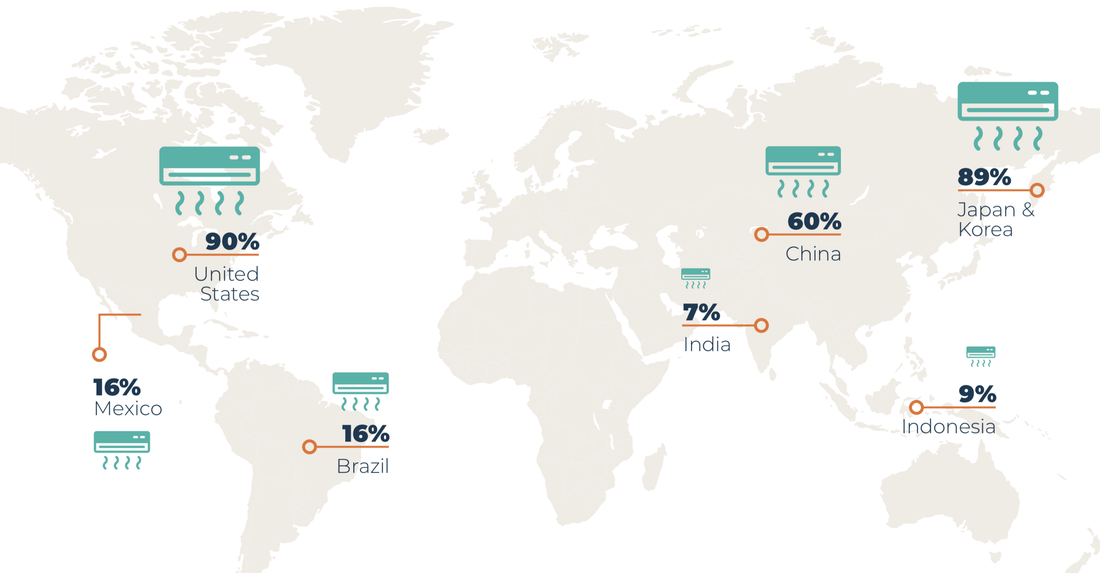

For most of human history, extreme climate events punctuated otherwise placid background conditions, with such impressive force or consequence that they were ascribed to the anger or vicissitudes of the gods (in fact, it could be argued that their existence spurred the need for explanatory supernatural beings in the first place). From droughts triggering uprisings in ancient Egypt to the sinking of the Spanish Armada to the extreme cold that thwarted multiple Russian invasions, extreme events not only strongly shaped contemporary happenings, but cast a long shadow that in some cases continues through to the present. In spite of this complexity of historical effects, the relationship was always unidirectional: climate affecting people. It's only in the 20th and 21st centuries that humans have begun to meaningfully affect the climate, introducing a new kind of complexity. This is often cited as a compelling reason for avoiding (or at least extremely carefully implementing) geoengineering — in addition to its unpredictable effects and the shifting political foundation that such efforts would rely on, there's an additional moral complication when a purposeful act results in a catastrophe. Suppose a devastating drought or storm could be traced to a geoengineering plan; could it be argued that the designers, funders, or technicians associated with the plan should be held responsible, that they should have known? A precedent about scientific foreknowledge (albeit a much-criticized one) was set in the infamous trial of Italian seismologists in connection with the deadly L'Aquila earthquake of 2009. The moral implications of 'natural' versus 'anthropogenic' (and whether such a distinction even makes sense anymore) are explored in a thought-provoking book by Bill Gail. Overall, doing something is at its very core viewed through a different moral lens than doing nothing (witness the famous runaway-trolley thought experiment), just as doing something purposefully is different than doing something accidentally. The lens one uses to approach anthropogenic climate change therefore greatly affects the takeaways of who's responsible and what's the optimal future course of action. Like most problems related to human civilization, environmental or otherwise, the challenge of adaptation to extreme climate events is multiplied by the number of people affected. Gathering the resources to support millions of people in need in the aftermath of a disaster remains difficult for even the most advanced societies, and often solutions involve more of the thing that caused the problem in the first place. An exemplar of both categories is air conditioning, as shown in the figure above. Invented for machines (not people), it has come to be the quintessential emblem of a comfortable lifestyle, in high demand across the world. These multiplying devices in a warming climate will themselves lead to so much energy demand as to cause an additional 0.5 C of warming by 2100. While that report is optimistic about the cost competitiveness of technical advances that would neutralize the negative effects of a 5x increase in A/C demand over the 21st century, others are not as sanguine. But from a moral perspective, how can something be used (to excess) by some groups of people and then denied to others? Even if we now know the externalities associated with e.g. cheap coal-fired electricity, it is not straightforward to argue that this means Indonesia's people in 2019 should be forced to use more difficult or expensive sources of energy than those that powered Britain's Industrial Revolution 10 generations prior. Clearly it is desirable to make efforts to enable economic growth and environmental protection to be compatible, but in cases where they truly conflict, that's where the moral questions are most pronounced.

Extremes, anthropogenic global warming, and geographic patterns of development all come to a head in urban climatology. In most cases (that is, in non-centrally-planned economies), people move to cities of their own free will, in order to pursue economic or cultural opportunities unavailable in smaller places. From a utilitarian standpoint, this is unquestionably good. From a climate standpoint, cities tend to amplify the challenges of extremes (particularly in a warming world), with the classic example being urban heat islands. The cost of an event, as well as the event itself, is often increased when occurring in an urban setting. On the other hand, both extremes and cities' effects on them have certain advantages. For instance, consider extreme cold (the kind that is currently enveloping the Midwest in a once-in-a-generation chill). The urban heat island aids in mitigating extreme cold, non-negligibly reducing its associated mortality and economic effects. This would seem to impose a kind of conditional goodness on urban warming that's a direct function of the ambient temperature. Yet it's not so simple as to say that extremes are 'bad' and moderate conditions 'good' (though one can't help but have a positive emotional reaction when reading about increasingly mild weather). Cold extremes help hold pests in check, while wet extremes are often useful in recovering from severe long-term droughts. Even if we had the knowledge and power to turn one knob to reduce some extreme, should we? And who would do it? And what would be the criteria they would use to decide? And what if something went wrong? The political, legal, and philosophical quandaries are endless, to say nothing of the scientific and technical ones. And yet, on the other hand, we are already engaged in a vast centuries-long unplanned experiment. No handbook on climate etiquette yet exists, though maybe we should be thinking along those lines, as individuals as well as governments, businesses, and other organizations. Furthermore, looking to a future where extremes and their effects generally grow larger and larger in a warmer world with more severe drought and floods, these questions become more urgent. As described above, they involve time-lagged inequality, the human-environment relationship, and the complex interacting effects of climate extremes. Certain of these aspects fall under the umbrella of 'climate justice', the recent movement to more explicitly consider the socioeconomic and cultural dimensions of environmental problems, and consequently press for socioeconomic and cultural types of solutions. Others are more complex. Regardless, new ways of thinking about climatic-anthropogenic feedbacks are necessary in a time when our power to shape the global climate is larger than ever before, so large in effect that not only our actions, but the externalities of our actions, strongly affect societies, economies, and ecosystems the world over. I am hopeful that the more we reflect on this moral problem, the more likely it is that we will come to solutions (at least, piecemeal ones) that mitigate the complexities our civilizational developments have brought into being.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed