|

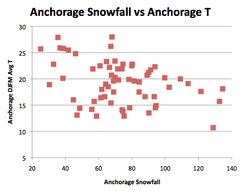

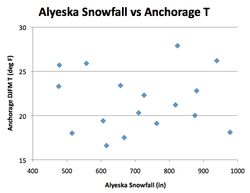

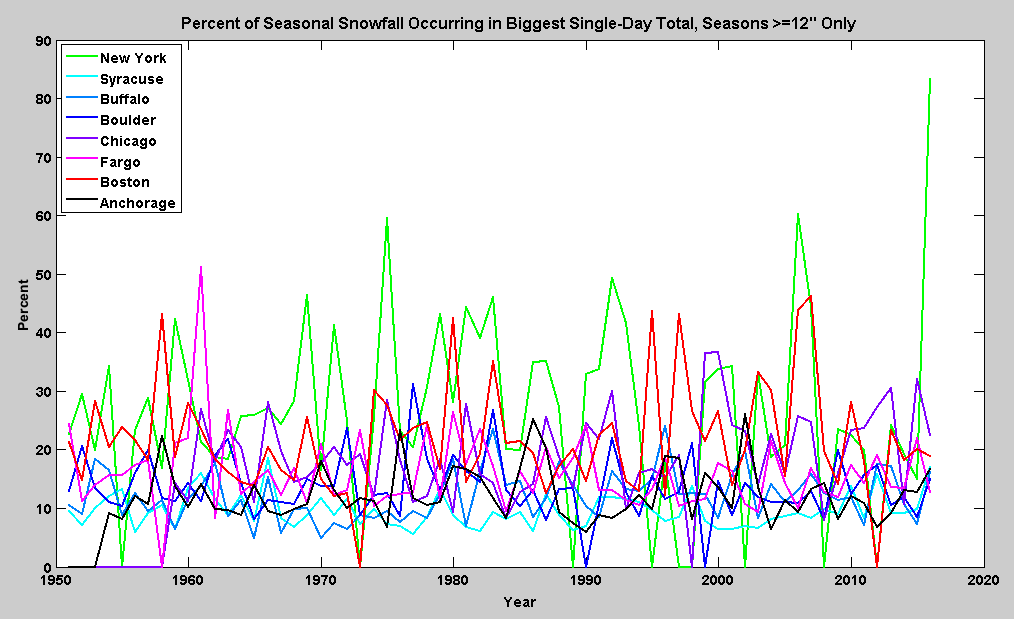

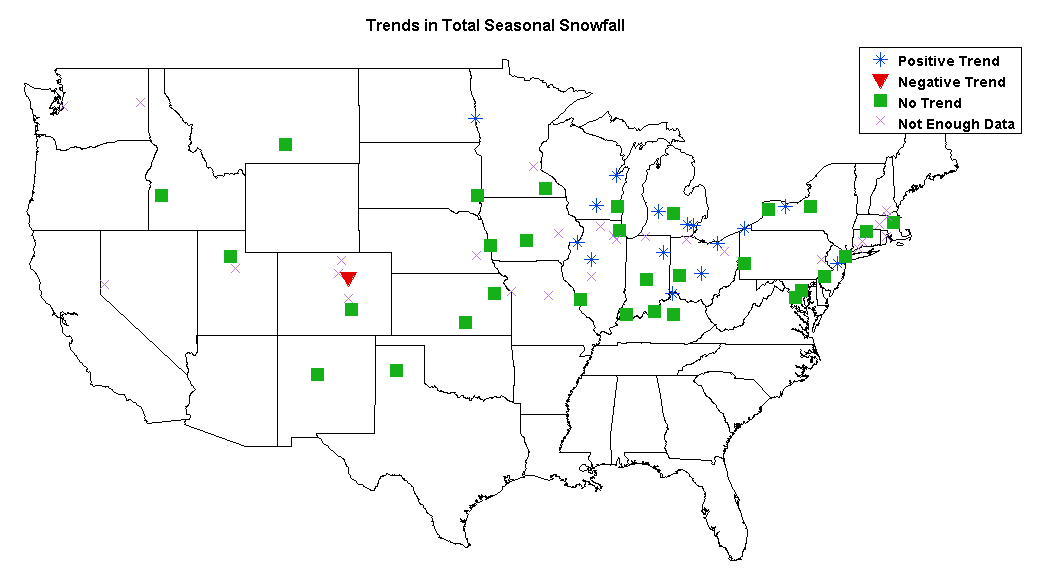

May: the season of flowers and baby animals and sunshine and snow-season recaps. Over on the Recent Weather page a summary of this winter's total snowfall and snowfall relative to climatology are posted for US cities, as well as the highest snowfall recordings around the world. Available data is spatially inconsistent but does cover at least part of all the major Northern Hemisphere snowy mountain ranges other than the Himalayas (i.e. Japan, Europe, and North America). This year's champion was Alyeska Resort south of Anchorage, which recorded 824" (2093 cm), somewhat above their average of 650". In second place was the weather station on the side of Mt. Rainier which registered 688"; the remainder of the top 10 consisted mainly of the western US, along with Kiroro resort in Japan and Zugspitze in Germany. A warm winter in Europe, especially in the first half, precluded more European ski resorts from joining the list — consistent with warm and wet conditions generally expected there during El Niños. Among US cities, Boulder won by a large margin, 109.7" to second-place Syracuse's 80.3". This was the fourth consecutive year that Syracuse was runner-up, continuing a record five-year dry streak for New York State's snowbelt cities. Given the projections made back in October, this underperformance of the eastern Great Lakes was to be expected, as were several other notable features of this winter's snowfall discussed below. Because of the strong El Niño, average to above-average snowfall was anticipated only in California, Nevada, and to a lesser extent the Southwest into central Colorado, with below-average snowfall arcing from Nebraska across the Great Lakes into New York State. The official NWS forecast along the Northeast coast was torn between the effects of higher precipitation and higher temperatures. This teleconnection-based forecast held true for the most part, with warm temperatures and dry conditions across the northern tier of the country, except for the Pacific Northwest where more precipitation fell than expected. But in Seattle it was never cold enough for snow, causing only the third snowless winter there since records began. Other stations with snowfall considerably below average included Billings (located in the dry spot on the October NWS forecast), Anchorage, and a small pocket of eastern Kansas and western & central Missouri. Anchorage is an interesting case as it is just 40 mi from the aforementioned Alyeska Resort, and only 2500' lower. However in a warm winter, and with the resort facing the ocean with the city in its rain shadow, these little twists of geography make all the difference. After a quick start (snow on the ground continuously from Oct 30 to Dec 28), Anchorage recorded just one day >=1 deg F below average from Jan 1 through Apr 30. Unlike Alyeska, Anchorage snowfall shows a clear decreasing trend with higher temperatures (see below), and that played out again in this El Niño-dominated year. Kansas and Missouri experienced a wet December but a dry winter after that, ending up as one of the least-snowy winters on record for Wichita, Kansas City, and Columbia, MO. They were expecting a somewhat snowier-than-average winter based on the El Niño teleconnection-based forecast, but the average storm track was further north than usual for an El Niño event, with (directly to their north) Sioux Falls, SD receiving its 5th-most snowfall. The Front Range in Colorado benefited from several spring storms, while the Northeast from Washington to Boston was subject to one big storm on Jan 22-24, and a smaller one in March in New England. Even for a region in which snowfall is concentrated in a handful of events each year, the dominance of that single event is remarkable: in 24 hours, 27.3" fell in Central Park, the largest single-day total on record there and a full 83% of the seasonal total of 32.8". This concentration far outstrips any previous storm/season ratio, as shown in the figure below. All this thinking about snow made me wonder what the observed snowfall trends are like across the US. After all, in many regions there is something of a tug of war going on, often between temperature and precipitation; between greenhouse-gas warming and aerosol cooling; and/or between long-term warming and natural interdecadal variability. The ultimate effect in a particular place typically depends on its idiosyncratic climate characteristics. For example, in the Great Lakes warming has increased water temperatures and decreased ice cover, increasing the potential for precipitation, but the increase in temperature has not yet been enough to convert much of the snow into rain -- resulting in greater lake-effect snowfall. (This is akin to observed increases in snow cover in the high elevations of the Hindu Kush, where precipitation is increasing but temperatures are still well below freezing.) At some indeterminate point in the future, scientists expect the balance to tip and snowfall to begin decreasing.

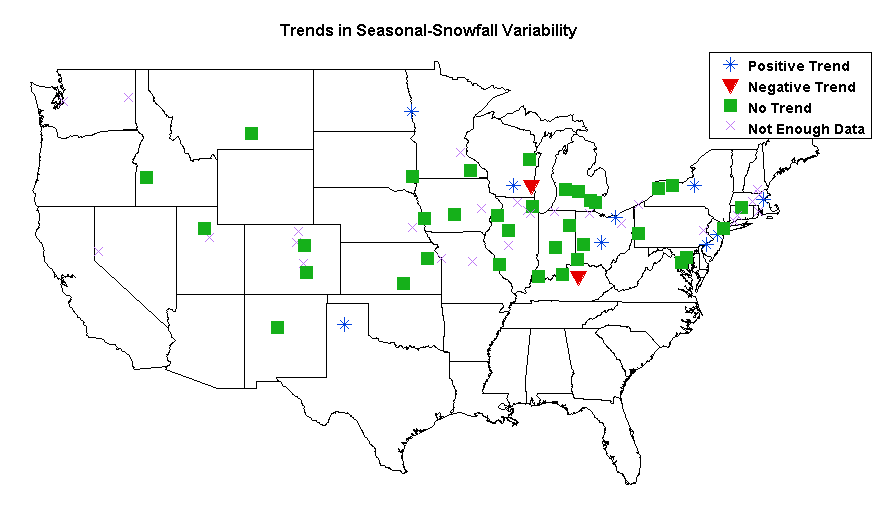

The trend in total seasonal snowfall over the period of record for each city (ranging from 50 to 104 years) is shown in the first figure below. At the 95% confidence level, increases are found throughout the Great Lakes as well as in a few other cities such as Fargo, while only one decrease is found, in Denver. Examining the plots for individual cities it seemed as if the increase might be in large part explicable by an increase in interannual variability in recent decades, and the second figure below partially confirms this. I defined variability as the standard deviation of a 20-year period of annual total snowfall, moved this window forward one year at a time, and finally computed a trend over these standard deviations. Looking now at the 90% confidence level, there are indeed increases for some of the same Great Lakes stations, as well as some stations on the Northeast coast, Fargo, and Amarillo. Milwaukee and Lexington, neither of which is substantially affected by lake-effect snowfall, exhibit decreases in variability. Speaking broadly, then, while there is some hint of increases in variability in parts of the Great Lakes and along the Northeast coast, the observed (mostly positive) changes in snowfall over the 20th and early 21st centuries cannot largely be explained by it. The climate has always been variable — it's more that now (to reference last month's post) we as a society have a greater expectation of insulation from nature's vagaries, and the ability through instant communication to pay more notice to extremes no matter where they occur. This past winter is an exemplar of that — while notable in the ways described above, none of the 73 cities tallied experienced a record high or low in snowfall, while because there are 66 years analyzed the most likely situation would have been one record high and one record low. Having strong computational models and knowledge of correlational relationships like El Niño teleconnections allow us to make better predictions, as borne out in October's largely verified forecast, but that's not the same as domesticating it — the climate is still wild at heart.

0 Comments

|

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed