|

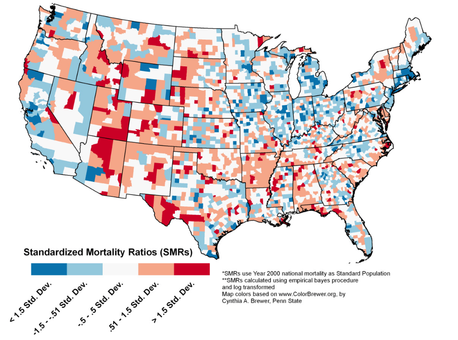

Here in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced last week an ambitious plan to substantially increase the city's affordable-housing stock. With continual upward pressure on housing prices, this is a welcome proposition. City planners are hoping that by increasing the supply of housing, low- and middle-income residents will financially be able to remain in the city. The problem is that many of the incentivized areas are low-lying and coincide with areas flooded during Hurricane Sandy (see interactive map at bottom). By comparing the income map (also below) with the inundation, it is apparent that as things stand today, flood-prone areas are dominated by low- and middle-income populations. Nor is this pattern restricted to the New York urban area: sociological studies have corroborated the perception that income is a robust predictor of vulnerability to and suffering from natural disasters, both between countries and within the U.S., due to housing location and quality among other factors. Of course, locations near shores naturally exhibit lower summertime maximum temperatures due to sea breezes, and are thus less dangerous to human health in that regard. In fact, the below map of county-level death rates from all 'natural hazards' does not resemble at all our preconceptions, which are based on faster and more-exciting media-reported disasters like tornadoes, floods, and hurricanes. Coastal cities like New York and Boston, and even hurricane-prone Miami, experience fewer deaths on a per-capita basis than arid, impoverished, sparsely settled counties in the West that are subject to extreme heat. As a slow-moving kind of disaster, sea-level rise is thankfully unlikely to lead to catastrophic death tolls; economic damages, on the other hand, are by all forecasts expected to be severe as seas inch ever higher. And, as has been seen throughout history, floods are squarely in the category of 'things that need only happen once to destroy a place' — unlike, say, heat waves, where some people die but the underpinning physical infrastructure is rarely damaged. So, as with many environmental dilemmas, the question of whether Mayor de Blasio's plan is a well-advised one can eventually be reduced to some form of mitigation or avoidance? Committing to make these huge investments in vulnerable areas amounts to doubling down on the bet that the region's defenses will be able to withstand the biggest storms of the coming decades, for as long as the buildings' useful lifetime lasts (and, if the past is any indication, probably much longer). If this amount of affordable housing can only feasibly be constructed in low-lying areas, then it is justified in the sense that the benefits outweigh the costs, with the benefits probably coming first and the costs becoming apparent later on. In the short-term, enormous economic benefits will accrue to the entire regionwide population of renters, who will enjoy lower rents, shorter commutes, etc. So it's an inherently myopic fix, but most plans are. However, when climates change and risks increase over time, this classic temporal discounting of the political kind should probably be used less — though this is a very difficult mental readjustment to make. There is also the consideration of whether global society should really be cementing a paradigm wherein people with less means are prodded into living in the most climatically at-risk areas. But to not carry out such projects with the excuse of climate change would be to completely forgo a certain amount of (economic) utility because of the possibility of disasters at some unspecified point in the future. Certainly, no plan or preparation is ever perfect. Models can give us the best-estimate probability distribution of flooding of a certain magnitude over a certain future time period, but weighing that information against other needs — like housing for economically squeezed residents — seems to still be best decided by human judgment.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed