|

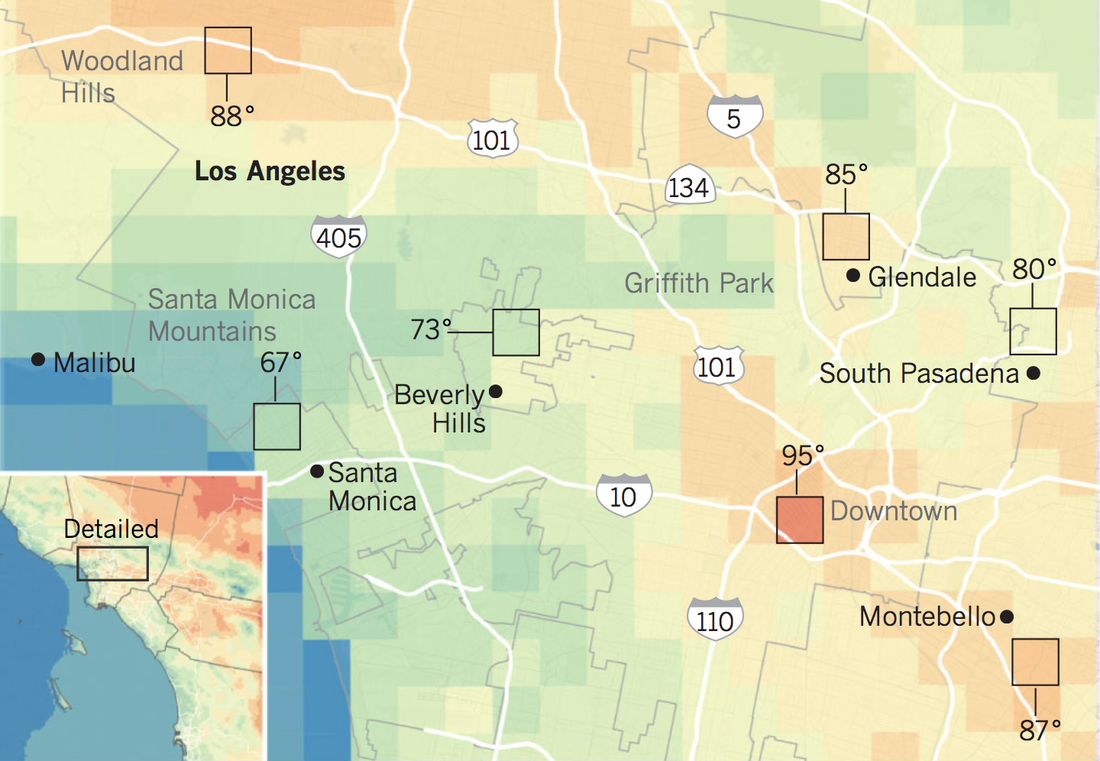

Making yourself scarce is in vogue — identifying and reducing carbon footprints, leaving no trace when visiting parks, restoring various natural environments, etc. This trend is in response to a long history of conspicuous consumption and attendant environmental damages. The imperative of economic development results in most every country having a clear pattern emerge as the arc of development progresses: build {buildings, infrastructure, industries, wealth} first, consider the consequences later. This applies equally to lives (safety regulations) and finances (consumer protections) as it does to the environment. Then, as people get more stuff, they get more conservative and have a greater desire to protect what they have versus acquiring even more. In Europe & North America, the development pendulum began swinging back from indiscriminate and cheap to expensive and more-carefully-considered around the third quarter of the 20th century, and there is some indication that it’s begun swinging back in places like China as well (somewhat ahead of expectations), but it’s still on its initial ramp-up in places like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In a sense, then, environmentalism in the real world is discretionary – desirable to everyone, but always decidedly in a mediocre position (at best) in the public’s list of priorities. As the environment improves, as it has in the US since the mid-20th century (whose unprecedented pollution and unfettered industrial activities prompted the first major environmental movement), the marginal value of additional investment and attention decreases. Concern for 'naturalness' has come in multiple waves, though, and it's interesting to note that the animating conservationist spirit of the 19th century in fact preceded large-scale industrialization, and how the modern emphasis on clean air, water, etc. is echoed in the ethos of that era, despite the interlude of a century of faith in the all-curative power of technology to liberate people from their surroundings. Whatever the exact reason, there is now a growing awareness of more-nuanced effects than burning rivers and black smog -- things like cardiac stress from increased heat, economic impacts of heat extremes (plus another paper on heat extremes), and greater infant mortality from air pollution. Below are three examples of cities that are experimenting with different ways of consciously shaping their urban form to reduce its impact on the surrounding environment, with the aim of making their economies stronger and citizens healthier. In essence, all three are bargaining that -- given the costs of environmental degradation -- doing something is not only morally preferable but in fact cheaper in the long run than doing nothing. In Los Angeles, concern centers on the effect of the urban heat island on human health. Scientists working with city planners are aiming to reduce extreme summertime heat by 1.5 deg K by 2040, which is comparable with the projected increase in temperature in the same timespan. There are theoretically well-founded methods of doing this -- whitening roofs, planting more vegetation, rounding off building corners to facilitate airflow -- but the sheer quantity and variety of built structures across Southern California, combined with the region's many microclimates, make it an especially challenging task. New technology, such as permeable and/or more-reflective asphalt, may come into play. The exact cooling strategy will likely differ from neighborhood to neighborhood, based on the current situation. For example, a canyon already has sufficient airflow, but a mid-valley spot may not; reflective asphalt will be less effective in an area where the streets are already shady. There is also the inherent push-pull between water conservation and temperature limitation, because water (via evaporative cooling) is the single most effective way to cool the air. And of course Los Angeles has a particularly tangled history with using water from other places for its own purposes. With the attendant complications, overcoming financial, technical, climatological, and political obstacles to reach the city's goal will be a demonstration of the feasibility of this cooling program just about anywhere that has the resources to invest in itself in this upfront manner, and that then need only watch the dividends slowly accrue over the following decades. In Barcelona, the aim is cultural as much as it is climatological. With the vision of recreating the vibrant pedestrian-oriented urban patchwork that was ubiquitous before motor vehicles came to dominate just about every block across the globe (not to mention the reshaping of cities to their specifications), streets in parts of the city are being eliminated to form 'superblocks' -- nearly-carless cities-within-cities. Public opinion is conflicted, naturally, but transportation officials are adamant that the idea is a net positive, in terms of traffic pollution as well as noise reduction, space for play, and more social interactions. These positives seem quite straightforward. But part of the trouble is that while Barcelona is known for its compactness, that same factor also restricts airflow, magnifying the effect of whatever traffic pollution there is. Further, there is the traffic-engineering maxim of 'latent demand', which posits that traffic will always swell to fill whatever space you allot it -- and by not banning traffic altogether (which would be very difficult indeed), critics fear the creation of traffic-choked boulevards that are disruptive but no improvement over distributed side streets. Lastly, there are concerns about accessibility, longer commutes, etc. that have yet to be fully addressed. In any case, if the experiment is deemed a success it is sure to be replicated many times over elsewhere, providing a new template for modern urban design.

And in New York, plans rely primarily on vegetation and its ability to cool the surrounding air by evapotranspiration as well as through direct shading of the surface. Some roof-whitening is also in the mix. There is an unmistakable socioeconomic dimension to this program, given the strong correlation between vegetation cover and household income that is present in New York as it is in most other cities. This correlation is compounded by another one, that between air conditioning and knowledge of/access to social & medical services on the one hand, and household income on the other. City officials have some additional metrics with which to decide how to direct their investment: the economic benefits of existing trees, in terms of stormwater interception, energy conservation (through cooling from shading and evapotranspiration), air-pollution reduction, and CO2 absorption, have been calculated and mapped (using US Forest Service formulas) for every street tree in the entire city. Then, weather observations can show the hottest areas, and, in combination with climate and tree-benefit models, allow precise estimates of the efficacy of placing trees and/or white roofs on a given city block, ultimately yielding a ranked list of the most-cost-effective sites. While there are other issues for which income and climate vulnerability are closely linked, in New York as elsewhere, addressing the longstanding problem of urban heat is certainly a defensible place to start.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed