|

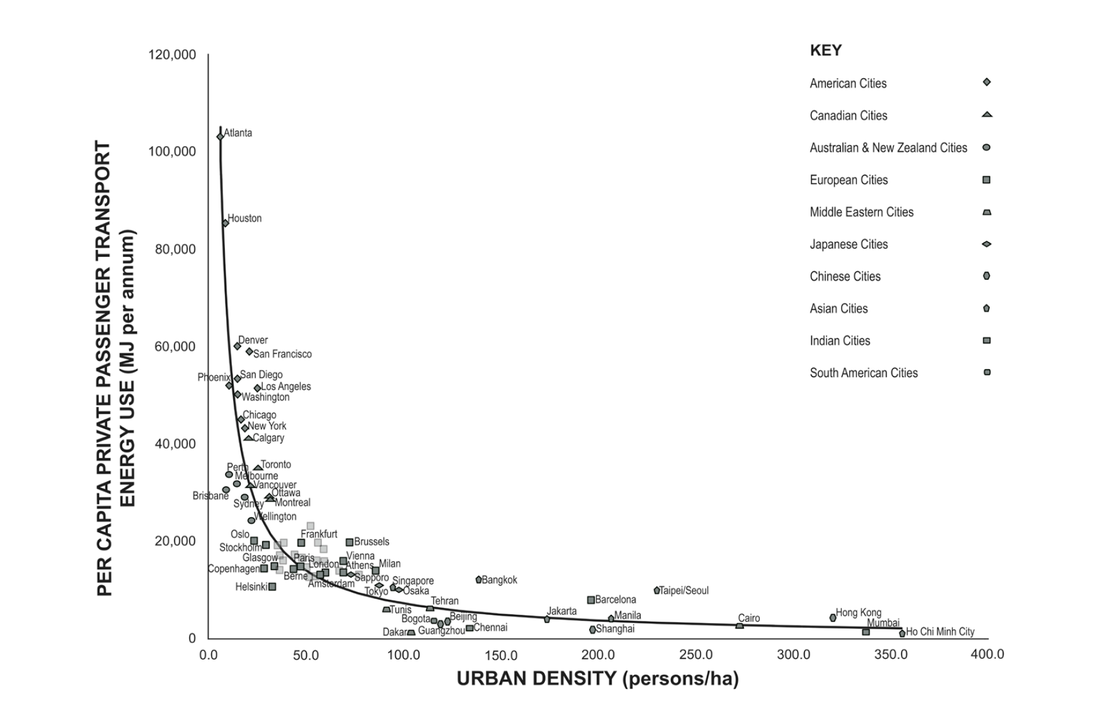

For our entire history as a species we’ve largely conceptualized ourselves as acting in opposition to Nature — improving it, bending it to our will — and yet (in a sense, paradoxically) there was always the assumption that this was a near-Sisyphean task, because Nature was so vast, its bounties so immeasurable, and its threats (disease, predation, exposure, etc) so omnipresent. Thus the frequent 19th-century references to the desirability of "improving the land", to the point of equating it with civilization itself, and the infamous stacks of bison bones, the dogged hunting of the right whale, and the heedless dumping of waste that, while ubiquitous, were recognized early on, by none other than Thoreau, as leading in an unsavory direction. The world was seen as a endless buffet open for feasting on industrial scales. In many ways, it is still that way now, more than ever before, due to the hugely greater population and associated demand for consumption that the planet now sustains. A simple perusal of satellite imagery confirms that as ground truth. In fact, the very concept of wilderness reserves (and even those are somewhat rare) would have been completely foreign to our ancestors only a few generations ago. Essentially, our species has become so numerous and technologically savvy that we've won the upper hand in the timeless struggle to survive in an indifferent environment. Along with that advantage come many implications, among them the realization that weather and climate are not just things that ‘happen’, à la Zeus, but things that can be shaped — to minimize the unintentional damage we've inflicted, of course, but also to achieve desirable outcomes for us (e.g. cloud seeding). An analogous realization happened long ago for the Dutch with their polders, where they succeeded in not only preventing their land from being further eroded, but managed to reclaim large tracts from the sea with technological advances and investments. This success represents a power and an opportunity, somewhat like a teenage parent overwhelmed by feeling like they have barely learned how to take care of themselves but have been entrusted with the cosmic duty of taking care of someone else as well. With this increasing awareness of responsibility come the first glimmerings of a strategy to address the underlying problem of the uncontrolled experimentation of pumping large quantities of greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the atmosphere and oceans — hence the Paris climate accords, among other actions. These have been accompanied, naturally, by reports of the many challenges such agreements need to overcome: political, social, financial, etc. Less reported on than some of the others is the effect of an inextricable linkage of development patterns with technology, which at a very fundamental level acts as a huge drag on the ability of society to 'decarbonize' (i.e. become more energy-efficient) at anything approaching a rapid rate. [The below figure provides a compelling illustration.] A recent paper stresses the point that making changes too quickly means 'stranding' assets, since for example a power plant that's only 10 years old has decades' worth of profitability left, profit that would be lost if it were to be mothballed. So, in addition to the direct effect of the long lifetime of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, this social/financial "lock-in" is another way that choices made now have ripple effects far into the future. In fact, it's difficult to imagine how the world might warm less than 2 C when the lock-in effect is estimated at being in the neighborhood of 1.8 C. In other words, if every choice from now on was made in the most environmentally sustainable way possible, but we continue to use the roads, buildings, power sources, vehicles, airplanes, etc. that we already have until they reach the end of their normal lifetimes, their combined emissions will cause something like 1.8 C of warming.

This large lock-in effect is only beginning to be appreciated and understood in detail, but it's clearly of the highest relevance for the climate of the coming decades. The situation could even be viewed as a version of the "Tragedy of the Commons", in that it'd be best in the long term if everyone who was capable of minimizing their emissions did so immediately, but it's in no one's financial interests to do so in the short term (at any particular moment) given the huge opportunity cost of losing out on the dividends of their current lifestyle. That's where strong, probably government-based, incentives would need to come in. On the analogy of nurturing 'infant industries' with financial assistance until they are strong enough to compete in the open marketplace, redevelopment could be heavily incentivized on larger and larger swaths of land until it had gained enough momentum to no longer need the artificial incentivization. This strategy could reduce the lock-in effect, but even so, it's a formidable adversary. Rather than battling pure Nature, as in the past, we're battling the jacked-up version of it that we've created. The present is the integral of the past, and in the realm of development patterns and their interactions with climate, that's true in very tangible and sobering ways.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed