|

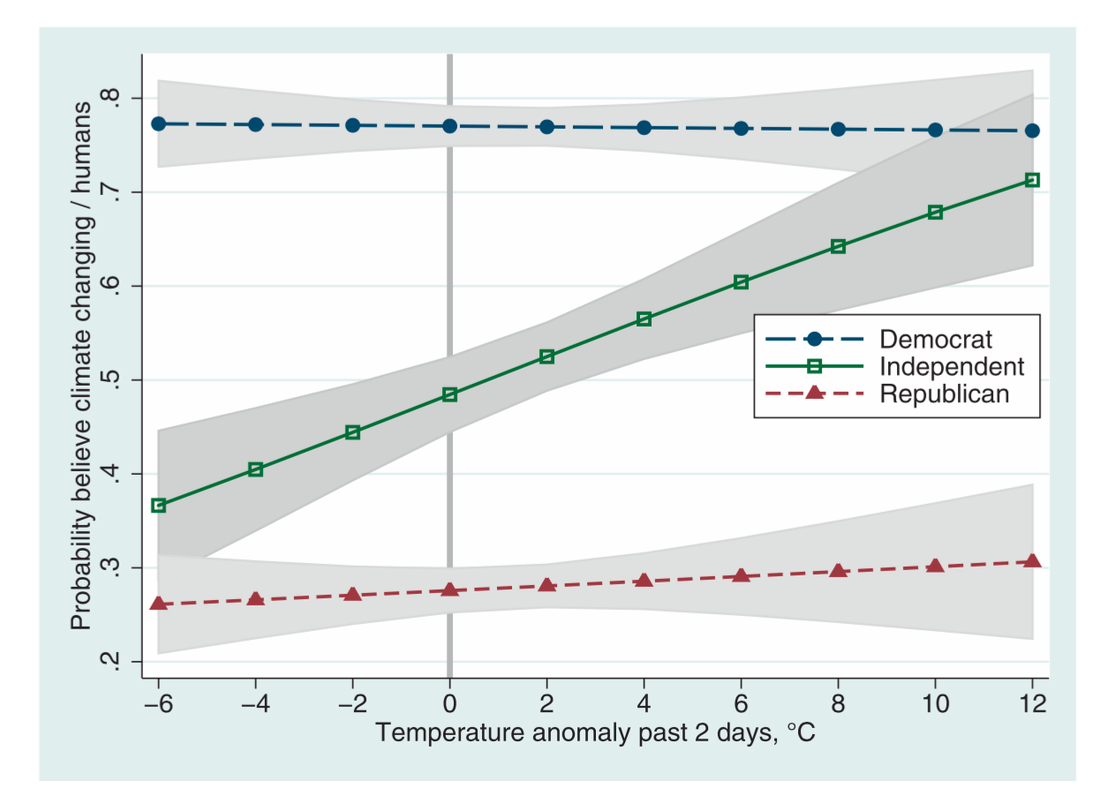

The faintest ink is stronger than the strongest memory — paraphrasation of a Chinese proverb In the world today, we have data galore, and yet many issues of substantial public policy are decided largely through the perceptions of the deciders, whether the issue is economic, climatic, or otherwise, and whether or not the perception is substantiated by the data. I write this post on the presupposition that the truth still matters, though some cynics may argue that narrative is now everything and reality is nothing. Part of the problem is that data is meek and tends to be overwritten (even among the scientifically literate and open-minded) by anecdotal-type perceptions that are dominated by memorable events and are in many cases not representative of the climate at a particular time and place. As a plausible hypothetical, the one year when there were two large snowstorms a week apart, and not the 5 years in between with no such storms at all. One recent study showed that perceptions of weather 5-20 years prior were pretty far off (the only category where people had any skill at all was for recent summer temperatures), except for flashbulb memories on personally momentous days, such as Danes' very accurate recollections, decades later, of the weather on the days of the German invasion and liberation of their country during WWII. For flashbulb memories, bias — where it exists — tends to be positive when moods are high (liberation) and negative when moods are low (invasion), termed the “pleasantness bias” by psychologists. In line with this, respondents from Colorado stated the weather on Sep 11 was worse than average, although in actuality it was sunny and warm across nearly the whole of the United States. These misperceptions are quite likely a function of several factors, such as the human tendency to remember the most ‘impressive’ thing (as it makes a better story), and the survivalist need to remember as much as possible about the conditions that surrounded an extreme, so as to be prepared for its next occurrence. People, not being machines, are also subject to heuristics like the availability heuristic of extending recent trends into the future, and in fact we often have more-accurate memories when the weather is pleasant.  An example of the corruptibility of human perception of weather & climate issues: for people who are on the fence about anthropogenic climate change, the percent professing belief increases linearly with recent temperature anomalies (Source: Hamilton & Stampone 2013, "Short-Term Weather and Belief in Anthropogenic Climate Change"). As a result, memories will never be entirely representative; however I think there are ways to leverage them to help people better understand their “personal climate history”, by linking their memories more clearly to the supporting data. For example, by pointing out where their memories and the data line up (and thus where their memories provide local color to the data), and where they don’t musing about the reasons why they remember something that is on the whole different from what actually happened on the preponderance of days. Establishing a trustworthy and viscerally true-seeming linkage between data and perception is in my view key for determining whether climate events, whatever and wherever they are, will be responded to proportionately and appropriately for a given location. One step in the direction of remedying this issue is the Common Sense Climate Index [CSCI], developed to quantify the 'feeling' people have as to whether or not the climate in their area has changed significantly during their lifetime. It is fairly simple in concept: it compares average temperatures and the frequency of extreme temperatures to the values they had in a baseline period, e.g. 1951-1980. When the index in a year exceeds one standard deviation relative to the baseline distribution, that means the year's temperatures would have been expected only out of every 6 years previously, and the devisers of the index presume this difference is large enough to be noticed by the casual observer. Four illustrative figures of the index are shown below; almost the whole world exceeded 1.0 in 2016, and it's been at or above 1.0 in recent years for the world, the United States, and many individual cities. Some areas, particularly those with high interannual temperature variability or land-atmosphere interactions, like the US High Plains, have yet to see a consistent upward trend. Endeavors like the CSCI are no doubt beneficial in the communication of science at a gut level, but this is not to say that memories should be discounted or considered passé as a mechanism of understanding climate. On the contrary, they play an essential role by filling in where data could not be obtained any other way, or exists but is of uncertain quality. A study in Iceland gives the example of diarists recording glacial positions, or encountering polar bears where none now exist. As this type of information is inherently qualitative, it is especially valuable when it describes something binary, where the accuracy is hard to dispute — someone either saw a polar bear or they didn't, no room for ambiguity.

Also, memories of climate are significantly better than those of weather, particularly among people who work the land and have a good sense of conditions in a place over multiple generations, and who have precise and unambiguous points of reference that they note as a matter of habit: dates of ice breakup, dates of spring planting, locations of glacial tongues, etc. Even so, quantitatively, the best correlation between recollection and fact is pretty imperfect. I'll close this post with some thoughts on how an index like the CSCI could be improved. Very simply, breaking out the components would allow people to see for example how extremes or particular months have changed in their region, helping them gain insight into the present climate (e.g. 'this past December seemed very unusual -- was it really?') and connect it with their own past. Another modification could be customizing the index based on a basket of indicators in each region that are regionally meaningful — special events, ski-resort opening/closing dates, days of snow cover, leaf-out dates, when the window A/C has to be brought out of the garage, the first autumn night requiring a winter coat, etc. Ideally, this would make the index maximally relevant to everyone's lives. Shifting the reference period for people of different ages, or those who have moved, would also help accomplish that goal. Finally, using more crowdsourced data, in the CSCI and in general, would likely stimulate greater interest and investment in local-climate problems, as people are always more emotionally tied to data they have a hand in producing and that they know matters to them. Scientists are trained to think that all data matters, but outside of science the relevance has to first be felt in order to be believed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed