|

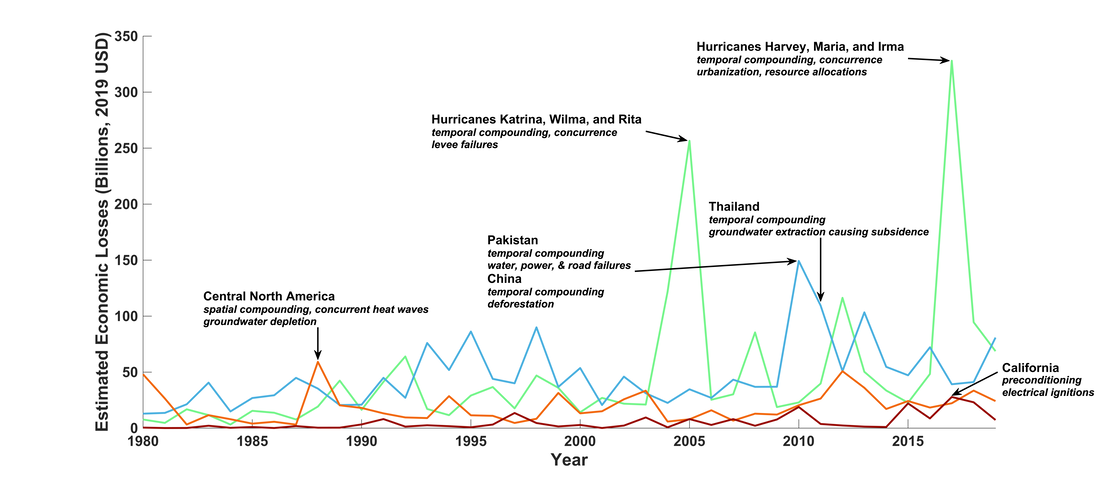

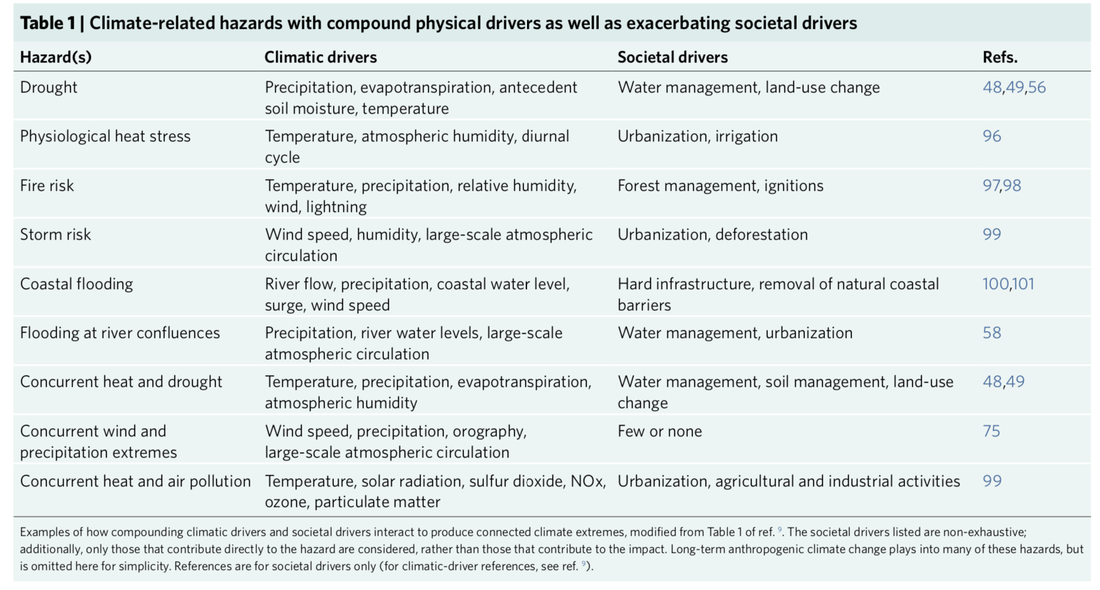

The ongoing, decades-long integration of non-atmospheric components into climate science takes many forms. This reflects increasing recognition of the two-way interactions by which climate impacts both modulate and are modulated by culturally based decisions, demographic vulnerabilities, societies' financial resources and technical capabilities, and so on. Simultaneously, the emphasis on mean change from the early IPCC reports has given way to a diverse bouquet of illustrations of how rare and geographically patchy conditions cause the lion's share of impacts in just about every way that we care about: health, ecosystems, economies, and societies. Even among extreme events, it is often multifaceted ones (or combinations of them) that are responsible for the most severe damages. These 'compound' events can result from intrinsic physical processes (as with the tight relationship between heat and drought in many places, or a single storm affecting coastal water levels in several ways), or from the more or less random co-occurrence of two events in close spatial or temporal proximity (e.g. wildfires followed at a lag of weeks or months by heavy rain). Sector-specific analyses, e.g. for food, hydrology, or insurance, have gone a step beyond physical hazards, by diving deep into relevant locations, actors, and relationships that affect risks. Along with work by the natural-hazards community, these studies have refined the concept of 'risk' to now encompass a nuanced portrait of how individual and sociocultural characteristics ('societal drivers') and physical characteristics ('climatic drivers') combine and interact to produce the observed impact from an observed event. Inspired by such ideas, in May 2019 I and others hosted a workshop at Columbia University exploring the dual frontiers of (1) characteristics of interacting extreme events and (2) how they affect human societies. Our new paper builds on some of the main threads of the workshop, but adds in what had been an overlooked element: how human decisions can amplify impacts relative to what they could have been, and in some cases can even feed back onto the severity of the event itself. In the terminology that we propose, these societal drivers transform an event (or event sequence) from being 'compound' to 'connected'; that is, interactions between events or event components can occur regardless of whether their physical hazards compound or not. The example we describe in the most detail -- because it was recent, well-documented, and catastrophic for those who were shortchanged -- revolves around Hurricane Maria's impacts on Puerto Rico in 2017. The island's existing vulnerabilities in terms of infrastructure and emergency-response systems were already laid bare when Hurricane Irma struck weeks earlier; Category 5 Maria added to the misery. But beyond that, bureaucratic inefficiencies and resource limitations on the part of the Federal Emergency Management Agency made for a slow and painful recovery, ultimately magnifying the long-term costs. Once the (admittedly complex) prototype is understood, examples abound. Multiple-breadbasket failure, for instance? Its likelihood is implicitly defined by, and thus modulated by, the places where crops are grown (and this could be changed in the future). Large wildfires primed by naturally dry years and climate-change-aggravated summertime heat? They're also primed by untrimmed vegetation, aging equipment, and land-use policies that allow or even encourage population growth in canyons and hills. In fact, the below figure from the paper illustrates how peaks in the timeseries of damages from four major types of extreme events are all straightforward to explain using this framework.  Paper figure 2: Major losses caused by extreme climate events over 1980-2019 and their connective elements, among tropical cyclones (green), floods (blue), droughts (orange), and wildfires (red). Annotations in high-loss years state some of the (first row) climatic and (second row) societal drivers that shaped the total impacts. Loss data are from Aon, Catastrophe Insight Division. In the course of writing the paper, we realized that intricacies of the type described above are not at all rare. They may only seem so because data limitations, and the intimidating nature of the multiple feedback loops that can be present, have restricted the number of reports that directly reference such interactions. However, it does not take much supposition to conclude that connected extreme events are an important and fertile area spanning the intersection of climate science, engineering, and the social sciences, and one for which we recommend some principles for effective research based on our author team's researcher and practitioner expertises. Chief among these is the recognition that, to be actionable, climate information must be provided in a way that is directly congruous to existing decision-making pathways (for whatever the intended application). Studies focusing on even a slightly different area, timescale, or variable are nearly impossible for stakeholders to integrate, considering that they have many responsibilities and considerations outside of the climate domain, as well as legal mandates and financial limitations. In other words, collaborations that lead to important impact-relevant research share many characteristics with collaborations among scientists: they must be carefully and deliberately constructed; not suck up all of either party's time; rest on a solid foundation of trust; and be flexible enough to recognize each other's interests and strengths, yet firm enough to mutually shape them. Storylines, stress testing, and ethnographic surveys are some of the promising yet still sparsely employed techniques for identifying research questions that sit at the junction of what can happen, what can be found, and what a decision-maker needs to know when it comes to connected extreme events.

Notwithstanding the topic's early stage, we conclude the paper on a note of optimism, relating that similar challenges have been successfully met in other contexts, and that it takes only having a sufficient incentive for people to come together and devise improvements to a functional but suboptimal status quo. The increasing severity and frequency of many types of climate extremes, resulting in a continual stream of new combinations of impactful and hard-to-predict idiosyncratic connections, hopefully provide that basis. Even without improved forecasts or projections per se, we are convinced that investing in better awareness about and allocation of resources for connected extreme events is more than worthwhile if it enables responses to them that result in recovery, innovation, and increased resilience going forward, rather than degradation of human and financial capital and a perverse widening of inequalities.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed