|

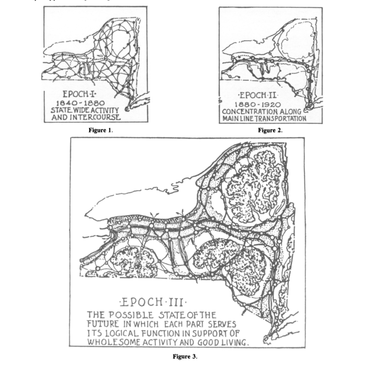

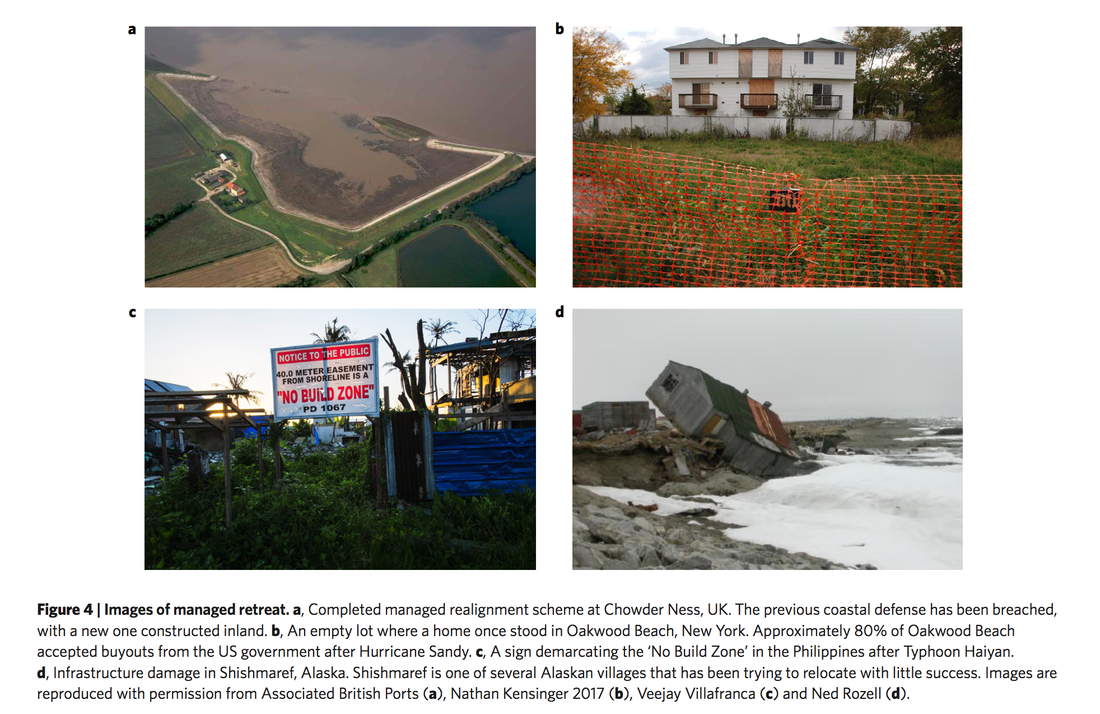

Resettlement, like migration, is a product of fragility. Unlike migration, it's typically coordinated and forced, rather than sporadic and voluntary. The fragility that spurs it can be sociopolitical (as with harried minority groups), economic (as with smallholder farms during the Great Depression), climatic (as along the Louisiana coast), or any combination of these. Where climatic fragility leads to economic fragility, making climatic and economic incentives consonant, self-initiated movement is most likely, even in the absence of a disaster per se. But typically, it takes a disaster, and even then few people want to leave their homes and neighborhoods if at all possible. This post examines resettlement in the 20th century United States and its implications for the future we all face, which includes the challenges of extreme heat, sea-level rise, and stronger storms (among others). To start, it's important to put resettlement in context. In a previous post, I explored the issue of climate-induced migration and resettlement in comparison with the adaptation measures that are more conventionally favored by planners. 'Adaptation' encompasses everything from human behavior to upgraded electrical grids and taller seawalls, and this will be sufficient for most of the population. The risks and costs of climate change are of course unevenly distributed geographically, but such is the raison d'etre of government -- to smooth out expenses and revenues across the full population, so that projects can be undertaken that are too complex, expensive, time-consuming, or unmarketable to fall within the province of private-sector activity. But of course government redistribution has its discontents, and particularly pertinent in the climate context is the disconnect between behaviors generated by current incentives and optimal behaviors from a utilitarian point of view. The basis of the objection is a simple economic axiom: the lower the cost of a good, the more of it is demanded, a prototypical example being taxpayer subsidy of the National Flood Insurance Program incentivizing the development of flood-prone areas. For the foreseeable future, much of this shared risk will probably remain politically and financially tolerable. But consider the most extreme cases: the sinking island, the isolated canyon community... these are the margins where serious public conversations need to be had about whether and how governments should provide an avenue (and perhaps additional incentives) for residents to relocate to less-fragile locations. The government thumb is already on the scales affecting where people live, in ways as varied as the infamous mortgage-interest deduction, the aforementioned NFIP, and the commitment to footing the entire bill for wildfire suppression without passing on any of the costs to homeowners. In the best case, climate-related challenges force a clear-eyed look at the purpose and consequences of these kinds of subsidies. If the major externalities are not internalized, market distortions and the resulting inefficiencies will continue indefinitely. Although inexact, the closest parallel to the present-day issues posed by ongoing climate trends is probably the 1930s Dust Bowl and Great Depression. There was in fact a short-lived "Resettlement Administration", under the umbrella of the New Deal, whose aim was to resettle farmers as a response to rural poverty brought on by a combination of antiquated agricultural practices and adverse environmental conditions (heat and drought). As the former program administrator described it, the driving force of the program was explicitly economic, with the aim of addressing the suboptimal productivity of labor and land that the small struggling Great Plains farms represented. Buyouts were extensive, but the new suburban communities for the displaced that were envisioned were never realized on any consequential scale. Despite support from many small farmers, these new developments faced ultimately crippling opposition on both financial and sociocultural fronts. This provides a valuable lesson for the present, in that it highlights the importance of considering where people will go and how they will be assimilated into a new community, beyond simply getting them out of harm's way. An alternative is to move a group of people wholesale from one place to another, as happened with both Native Americans and African Americans. That neither example was terribly successful points to the critical role of economics, in addition to community cohesion.  An idealized 1920s vision of the progressive optimization of land use in New York State, with substantial implied movement of people from the less-productive to the more-productive areas. The report argued for government-managed resettlement to speed along this process and improve the economic fortunes of the poor in the less-productive areas, even without the motive force of climate-related disasters. Source: Jacobs 1989, quoting Mumford 1925. At the same time, state initiatives were begun to alleviate the primarily economic hardship being suffered by smallholder farmers in the Northeast. With advances in technology and transportation stemming from the Industrial Revolution, their farms were no longer economically viable due to inherent climate and topographic factors, but many were trapped by debt. A decades-long political debate ensued between the 'social Darwinists' (advocating resettlement of the affected) and the 'repopulationists' (advocating investments allowing them to adapt to the changing times). The former group prevailed and buyouts began in earnest in the early 1930s in New York State under the governorship of FDR, who saw them as efficient ways to manage growing rural malaise. This is one of the few examples where a potential humanitarian disaster was foreseen and successfully avoided. However, they lasted just a few years before funding was cut back to skeleton levels.

A humbling lesson from these past efforts is that even in an era of substantial climatic stress and economic upheaval, these programs' achievements were ultimately narrower than their original visions. Key elements that seem necessary for long-term success are the preservation of some kind of social fabric, a plan for economic integration into the new community, and having community buy-in from the outset. A reliable and continuing revenue stream is also necessary from a programmatic point of view. Looking to the future, the social-fabric issue seems particularly pertinent given rising inequality, especially in urban areas. Exacerbating it is the fact that, even without climate stressors, the wealthy and highly educated are much more mobile and have more transferable skills, so that the economic and social shock of resettlement is smaller for them. This means that the poor are often forced to make larger changes in response to climatic threats, despite not having the resources to comfortably do so. Subsistence farmers are arguably the worst off, being highly vulnerable to climatic whims, having the fewest resources, and having a livelihood which depends on the scarce resource of land (as opposed to practicing a trade or service-based skill). Fortunately, some efforts are underway in the international-policy sphere to smooth out the expected necessary transitions -- in fact, there's even a non-profit organization expressly dedicated to facilitating climate-related displacements. Climate and social-science researchers are brainstorming solutions, and localized efforts have been implemented and largely proven successful, though in all likelihood large-scale initiatives will only begin when the true scale of the issue comes into focus. While not something that's likely to affect most of us, the exigencies of resettlement will have a large-enough impact on those who do experience them that we all should be interested in finding efficacious and cost-effective solutions. While climate change exists on a bigger scale than anything seen before in human history, no disaster has ever been purely natural (including the Dust Bowl), which should give us heart that the answers are not out of the realm of experience either.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed