|

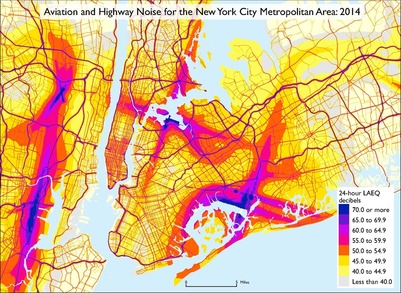

What comprises climate? It can be considered loosely but succinctly as the study of air: its properties, movement, and composition. Such major elements of study as temperature, precipitation, clouds, wind, radiation, and air pollution all fall under this definition. Rephrased, climate science consists of the study of anything that occurs in the atmosphere or is directly connected with or affected by the atmosphere, and on timescales long enough for meaningful statistics (typically at least several years). But there are some additional atmospheric phenomena not traditionally studied as such that nonetheless have bearing on subjects that are in the more traditional climate purview. In fact, they are so common as to be absolutely mundane: light and sound. Sound is the main casualty of simplification in the primary set of equations used in atmospheric science and particularly in modeling, for the reason that otherwise models would have to simulate energy moving very rapidly between gridcells and this would require very short timesteps, making the whole modeling enterprise considerably more computationally intensive. As they bear little energy compared with other wavelengths, they are routinely neglected. But that's not to say that they are inconsequential: sound is a critical medium for many animals as well as humans, affecting their ability to do everything from attracting mates to finding food. Animals that use sonar, of course, are particularly vulnerable. For these reasons and others, the European Environment Agency has set a goal of reducing sound pollution 'significantly', while acknowledging attainment of this goal in the near future is highly unlikely. That is mostly because the major sources of anthropogenic sound pollution, vehicle and air traffic, are increasing or remaining constant. It is also worth noting that natural environments can be quite noisy as well -- tropical forests, for instance -- but that the key is that organisms there have adapted to the noise, whereas those in other biomes generally have not. Likewise, while visible light is of course an essential component of radiation, and its effects on atmospheric temperature are well-characterized by observations and models, its effects on ecosystems (and thus indirect effects on climate) are very rarely considered. A study from 2014 makes the point that tropical bats avoid areas with even small amounts of light pollution, and that this avoidance spells trouble for plants in fragmented forests that rely on bats' seed-dispersal proclivities. The resultant potential change in forest cover further implies an impact on traditional climate metrics like temperature and precipitation, given the strong positive-feedback relationship between deforestation and future drying. A direct effect of light pollution on plants has been observed (at least in terms of correlations) regarding springtime budding in the UK. It's not hard to imagine other similarly complex but very real linkages connecting changes in animal or plant behavior due to artificial-light exposure with aspects of local or regional climate. On the non-traditional impacts side, many of the studies that have been produced concern temperature. There are several reasons for this focus: it's easily measured, constantly affects us (unlike, say, precipitation), varies widely across the globe, and not infrequently reaches values that we find uncomfortable, if not outright dangerous. Indoors, high nighttime temperatures are closely linked to sleep disruption in the U.S., despite the widespread availability of electricity and air conditioning. The effects are particularly strong among the impoverished and the elderly, and cannot help but be read in the context of the extensive medical literature implicating poor sleep in a host of maladies. Indoors, warm wintertime indoor temperatures are perhaps too comfortable, suggests a study pointing to lower caloric loss through metabolic heating than in decades and centuries past. Pleasant temperatures and sunshine, on the other hand, have been shown to improve cognitive performance.

While traditional ways of measuring climate and its impacts are deservedly predominant, it's often instructive to at least consider the other ways in which the atmosphere and life on the surface of the Earth interact. These are often more complex than they would seem at first glance, which is part of the joy of this field of study. And just as health and environmental impacts are maximized in urban areas as measured by traditional metrics, so too are they maximized there by non-traditional ones, making consideration of the factors behind them worthy of at least occasional consideration in an era when our ability to understand and consciously work to modify the interconnectedness of climate, economics, health, and the environment is increasing year by year.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed