|

On some level (in particular, the top-of-the-atmosphere level where net-global accounting is done), the effects of greenhouse gases are simple: because they trap outgoing radiation from the surface, the planet must warm to radiate more by Planck's Law and remain in equilibrium with the incoming solar radiation. This instantaneous 'radiative forcing' mechanism is relatively well-understood, although the subsequent heat transports and the final regional climate effects in equilibrium are less so. Radiative forcing occurs more or less uniformly around the globe, hence the term 'well-mixed greenhouse gases' [WMGHGs] for CO2, CH4, N2O, and several others that, once emitted, exist in the atmosphere for decades or centuries and move all around during that time. For near-surface air pollution, this is not the case. [Air pollution can broadly be thought of as any gas or suspended particle that is harmful to human health, and so is of most interest at the surface.] The compounds comprising it, like ozone, sulfates, and nitrates, have short lifetimes (a few days is typical) and thus are present in high concentrations only in or immediately downwind of source regions. This makes prediction more difficult, and of course also means that the differences in impacts between regions are larger.

Another fundamental difference between greenhouse-gas 'pollution' and air pollution is the divergence of their trends in recent decades: the former is generally still rising, while the latter is falling, at least in developed countries, as a consequence of strict legislation. Today's pollution hotspots are in places like Harbin, China and New Delhi, while the legendary suffocating smogs of Los Angeles and London -- that in terms of some components like sulfur dioxide were multiple times worse than even present-day pollution episodes in East Asia -- are mostly a thing of the past. To give a flavor of the severity, for the week ending Dec. 13, 1952, average SO2 concentrations in London were five times higher than the daily maximum recorded during Beijing's severe episode in Jan. 2013, resulting in something like 10,000 excess deaths. With such short lifetimes, these kinds of regional-pollution events respond to economic fluctuations, with impacts on the health of our most vulnerable citizens measured in the thousands, in addition to exhibiting seasonal patterns in intensity and location both in the U.S. as well as in China. And like smoking and obesity, it seems the more one reads, the more correlations one discovers between air pollution and elevated health risks: diabetes, for example.

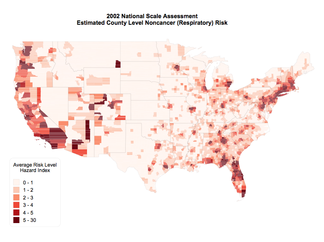

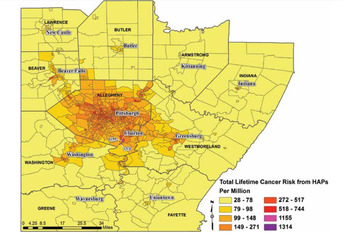

So, in a practical/political sense, regional air pollution control should be easier to agree on because the benefits of management are more immediately tangible. It's a case of big costs and big benefits, and politicians tend to dwell more on the first, which is why there is hesitation to impose regulations despite the consensus net benefit, and also why it is only once countries reach a certain level of wealth that they begin imposing limits on pollution of their own accord. The decision is often a conscious one: at low income levels, the benefits are judged as outweighing the costs, but this analysis changes with income (i.e. following a Kuznets curve). Is there reason for optimism then? The overall downward trends in the developed world suggest there is, although this optimism must be tempered by the recognition that reducing pollution might result in other unintended and undesirable counter-effects like increasing temperatures over the Atlantic that have been held down by reflective sulfate aerosols. Also, increasing summertime temperatures will promote the formation of more photochemical smog, especially in already-polluted urban areas. In the near-term, traditional foci of air pollution like coal-fired power plants and smelters continue to have significant negative health impacts on people living in their vicinity -- which is suggested by the figure at left below, and even more so by the figure at right. The values over 1,000 expected cancer cases per million residents in the righthand figure are in census tracts adjacent to steel factories. These are the scales on which people are affected, and so must be the scales ultimately considered in policy decisions if future progress is to be as remarkable as what has been achieved since the palette of London smogs included Madeira wine, yellow, dun, heavy brown, green-yellow, and faint yellow. At the bottom of the page is an interactive real-time map from aqicn.org, a group in China that compiles observations from around the globe into user-friendly formats using the EPA 0-500 scale for overall air quality. It works best in Firefox or Chrome.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed