|

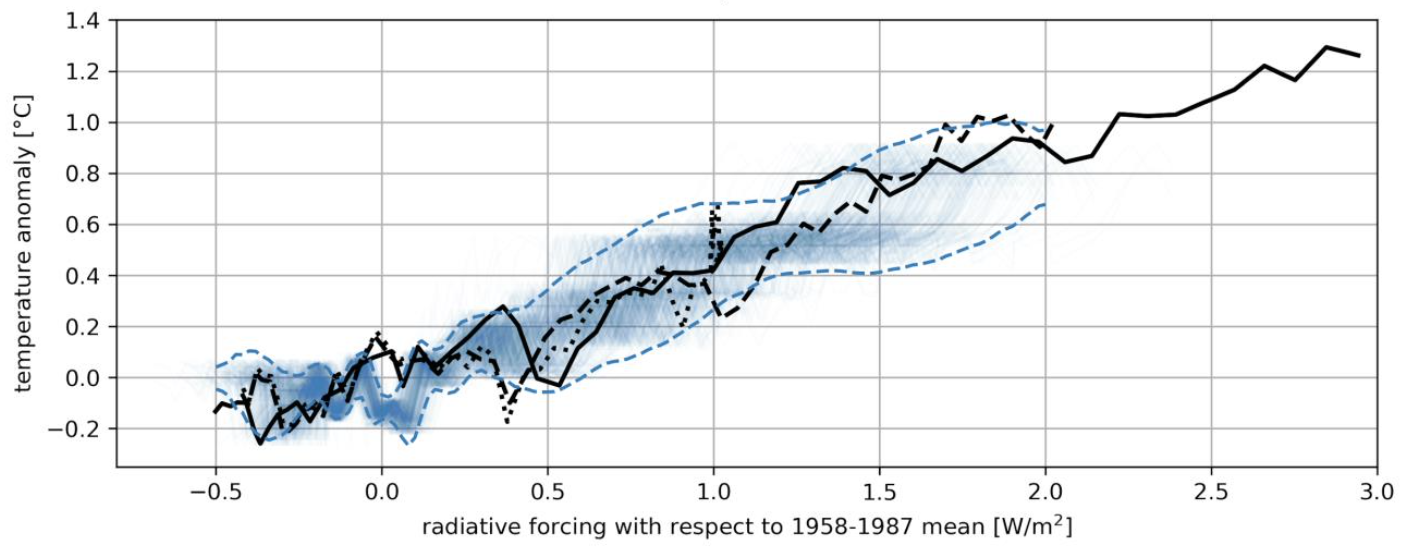

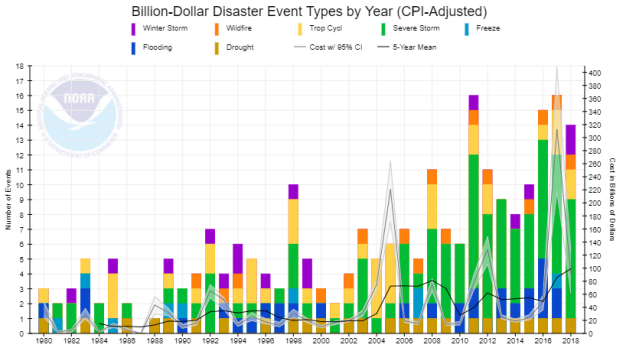

A personal, subjective attempt at summarizing the top climate stories and advances of the decade that has been: Climate models continued to prove very good at predicting global temperature change from greenhouse-gas forcings, and total emissions continued to track the top-line emissions scenario. Temperature increases led to 8 of the decade's 10 years ranking in the top 10 warmest years since 1850. A recent review paper looking back at studies from the late 20th century found that even the simpler, coarser-resolution models then in use predicted temperature changes entirely consistent with what has since been observed. The similarity across generations of models gives further confidence to global-average statistics such as mean annual temperature changes. It is sobering but not at all surprising, given the strength of the economic, social, and political status quo, that efforts such as the Paris Agreement of 2015 have not yet made any appreciable dent in the irrepressible upward track of greenhouse-gas *emissions* (not to mention concentrations), and thus that global-average temperature records continue to be broken left and right. A variety of severe extreme events, often distinguished by their long durations, inspired new efforts to understand and mitigate them. Several such events made their mark on the arc of history by striking wealthy and/or populated areas, rather than by their geophysical rarity. These included the 2010 Russian heatwave, 2010 Pakistan floods, 2010-11 Queensland floods, 2011 Thailand floods, 2012 Midwest drought and heatwave, 2012 Hurricane Sandy, 2014 and 2015 US Midwest and Northeast cold snaps, 2015 and 2018 European heatwaves, 2017 Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, 2017-2019 California wildfires, and ongoing 2019 Australia bushfires. Some were notable more for highlighting to physical scientists aspects of climate variability or change that were previously underappreciated (such as the much larger rainfall amounts associated with slow-moving tropical cyclones, or the mid-latitude effects of Arctic sea-ice melt), while others made headlines for their dramatic economic or ecological effects (such as the vulnerability of international supply chains to floods or storms). The now-ubiquitous Internet, and in particular social media, enhanced the power of some events by making the visual evidence of them compelling and unavoidable. Areas from agriculture to international trade to urban planning were increasingly shaped by the recognition that these kinds of extreme weather and climate events pose major (and in many cases growing) risks which it is imperative to address. Weather and climate computer models enabled qualitative as well as quantitative improvements in representing the Earth system, across a spectrum from basic research to public-facing operational forecasts. Probabilistic forecasts of storm surge and fluvial flooding hour by hour and house by house. Continuous global 3-km hourly weather forecasts. Quantifications of how the land surface affects the development of individual severe storms. Near-real-time estimates of the fractional contribution of anthropogenic effects on the characteristics of a natural disaster. Robust partitioning of observed regional climate changes into deforestation, irrigation, urbanization, global greenhouse gases, and major modes of variability. All of these were well beyond the limit of scientific and computational capability before the 2010s, but have now come into their own. A safe bet is that the 2020s will see many more such successes, each of which allows us to see 'around a corner' that had previously been blind. The pipeline from research to operations moves haltingly, but on a decadal basis the progress is clear, even if in ways that don't garner much publicity. And now, on to the 2020s! They present at the same time the largest-ever opportunity for human development and for furthered understanding of the physical climate (and how the two-way links between it and societies function), as well as the largest-ever risks from the potential misallocation of financial and intellectual resources in the face of rapid ongoing changes. As the world continues to become larger and more complicated, a certain level (even minimal) of harmony and collaboration within and among the international research and policy communities would greatly ease our ability to constructively manage the enormous task that we have effectively set out for ourselves as a species: to be, for the foreseeable future, active and conscientious guardians of an entire planet.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed