|

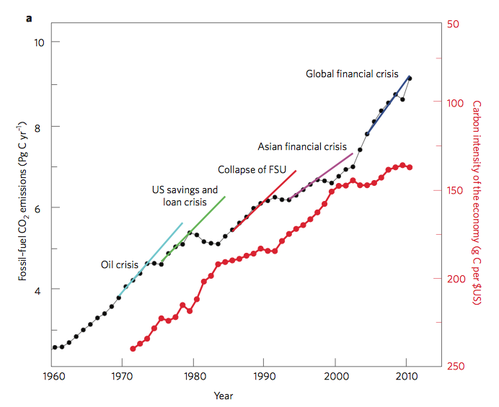

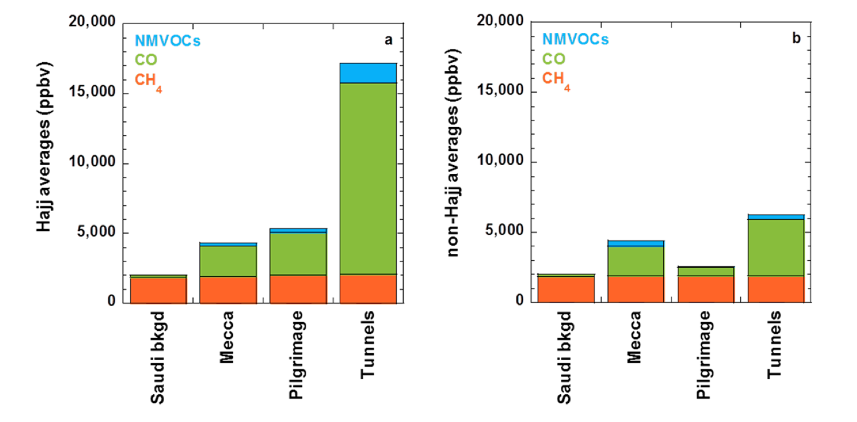

Two articles ("Holiday Lights from Space" and "A Hazy Road to Mecca") in the December issue of the Urban Climate News highlight an important aspect of climatology, and of urban climatology in particular: the wildcard of human influence. Some climate decisions can be strongly influenced by human relationships writ large, of course, as is always the case in geopolitics; but the phenomena described in the two articles above cause us to reflect upon the ability of ordinary people to together modify the environment around all of them when behaving in a coordinated way. Holidays are a perfect example, whether they mean a person treks to Mecca or simply sets out decorations in their yard. Analyzing the changes during holidays are fun, but, more importantly, time variations allow for a better understanding of how sensitive the climate system is (on local and regional scales especially) to human actions. The midweek peak in southeast-U.S. precipitation is one good example of this. Zooming out to the scale of years, economic crises leave their signature in emissions trends as well. It's not just in or near cities where the human temporal fingerprint can be detected, but any place where people gather in numbers for a length of time and bring with them the trappings of an energy-intensive lifestyle. (This is to a certain extent just a case of the general rule that adding more people can turn any previously sustainable activity, like slash-and-burn agriculture, into an unsustainable one.) The authors of the study examining environmental conditions along Hajj routes ingeniously made the connection between the huge concentrations of people — however temporary — and the probable resultant impacts. After all, from a human-health perspective, the degree to which adverse conditions are problematic is proportional to the product of their severity and the number of people exposed. Indeed, the study found that heavy traffic, constrictive tunnels, and high temperatures were the main factors in producing locally extreme levels of carbon monoxide, methane, and toxic volatile organic compounds [VOCs]. These spikes were not representative of regional conditions, but the 100- or 1000-km average isn't what matters for something like air quality; the 1-m average is. I don't expect that models will be able to soon, if ever, capture the effects of traffic jams in Meccan tunnels on a handful of days surrounding Ramadan. But keeping in mind that goal lays out a useful scientific trajectory for, in the coming decades and beyond, moving from bulk averages to localized and fleeting values.

Achieving that goal calls for more inspired studies that look at temporary perturbations to the time- and space-average anthropogenic climate effect. Typically, regional studies focus on the space average, or the time average but primarily for periods defined by ambient environmental conditions like heat waves. Both require parameterization to get down to the level of human experience, which is something like one meter in space and one minute in time. Although perhaps clearest for air quality, I think there is a purpose to closer examination of other types of detailed time-varying climate information as well. The amount of lights during holidays may be a proxy for overall increases in energy usage, which would have implications for the management of electrical capacity, especially when two stressor events overlap (e.g. a hot holiday afternoon). Large events like festivals or games, whether in urban areas or far away from them, may also have discernible environmental effects for attendees or residents of the surrounding regions. Or they may not. The point is, in a world of 'smart' and 'just-in-time' allocation of resources, such questions are not just worthy of consideration from an impacts standpoint — they may be able to tell us something useful about the behavior of climate systems as well as that of ourselves.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed