|

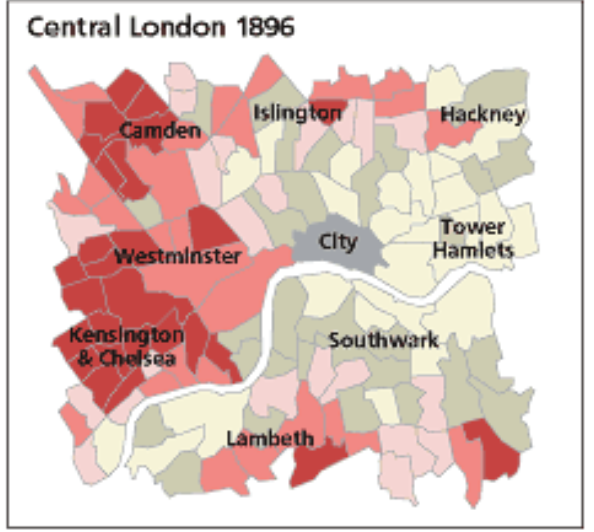

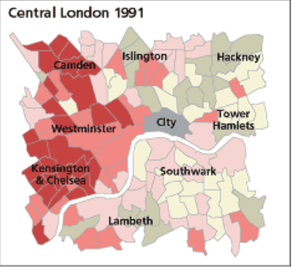

On the largest scale, we all know from common experience certain aspects of the geography of wealth. For example, that there exists a strong correlation between latitude and wealth. But on the smaller scales, too, we see patterns emerge that are just as strong. For example, whatever way the arrow of causation points, it nearly always results in the poor living in the most climatologically undesirable areas. Perhaps it is that the neighborhoods near power plants, major highways, etc. are cheaper and the poor are shunted there; perhaps it is that the poor are less able to protest and politically prevent the erection of sources of pollution in their neighborhoods. Many examples of both surely spring to mind. In combination, they mean that the poor live in areas where the mortality may be as much as 2.5 years less than the area mean (see figure below). The wealthy dominating certain climatologically favored areas is hardly a phenomenon of the industrial era. The Latin poet Martial wrote: "While the crooked valleys are crowded in mist, [the villa] basks in the clear sky and shines with a special radiance of its own... From here you can see the seven lordly hills, and can survey all of Rome, the Alban hills and those at Tusculum, every cool suburban spot." A study documenting socioeconomic patterns in American cities in 1880 found that household wealth was positively correlated with elevation -- hypothesized reasons include views, breezes (in a pre-air-conditioning world), privacy, and the prevalence of stagnant water and its associated diseases in the lowlands. To a remarkable degree, worldwide, most slums are in swampy lowlands, from the East End of London to the Lower East Side of New York to Lagos and Mumbai. The wealthy congregate on hillsides, from Mount Royal to Hollywood to Yamanote. Only in unreconstructed areas that are rocky, very steep, remote, significantly colder, or otherwise forbidding, do the poor live at higher elevations. Examples of this include the present-day area of Central Park prior to the park's construction, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, and the city of El Alto, Bolivia vis-à-vis La Paz in the warmer valley below. Besides elevation, another strong correlation is between geographical direction from the city center and wealth. Because in the mid-latitudes of both hemispheres winds are typically from the west, pollution from the city tends to be blown to the east, such that from the dawn of industrialization there has been pressure in many areas pushing the poor to those disadvantaged areas. The insidiousness of this type of silent urban geographic molding is that once formed, it would take enormous effort and expense to change it — so it endures, at great social cost. The wealth geography of London has hardly changed in a century (also see below), even though in absolute terms the pollution is much less than before (in the case of London, the East End has been doubly disadvantaged by the fact that the Thames flows from west to east, transporting foul water in its direction). It is fascinating to note how technological advances have muted some of the traditional correlations, while future factors such as sea-level rise will shift the goalposts of the game yet again. Reductions in pollution, plus better filtration, have in many places lessened the imperative for avoidance of the city centers. Air conditioning has reduced the climatological incentive to have breezy, cool buildings, and encouraged the growth of insufferably hot cities such as Phoenix. Mosquito control, vaccines, and improved drainage and hygiene more generally have, in the developed world, mostly eliminated the intra-urban correlation between elevation and stagnant water. This has meant new construction in many areas is often in these previously undesirable or simply unbuildable areas, although it may take hundreds of years for the shift to complete. For example, in Midtown Manhattan the bogs were drained and the vegetation felled in the 19th century, yet the undesirable label stuck with the lower ground along both rivers, leading to these areas being filled with tenements, auto-body shops, warehouses, and the like throughout the 20th century. Only now is wealth pouring in and tall buildings being constructed. Yet sea-level rise means that inevitably, perhaps within decades, these gleaming new buildings may be threatened and (to speak punnily) the tide may turn again on these reclaimed lowlands.

While the prototypical "castle on a hill" urban template is long gone, there were solid climatological reasons for the wealthy to retain the high ground in most places, and relegate the poor to the low ground. This is primarily a response to the strong correlation of elevation with desirable traits such as clean air, water, and safety from flooding. While recent advances have rendered most of these reasons obsolete ipso facto, the inertia of urban geography is great, and there are additional factors such as the siting of polluting industries and activities. As long as it continues to be politically palatable to favor the rich over the poor, this corrosive environmental inequality will endure. But the better our understanding of its patterns, and the microclimatological influences that are the mechanisms for its deleterious effects, the better those effects can be managed and the tyranny of place less of a strong force in shaping people's lives.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed