|

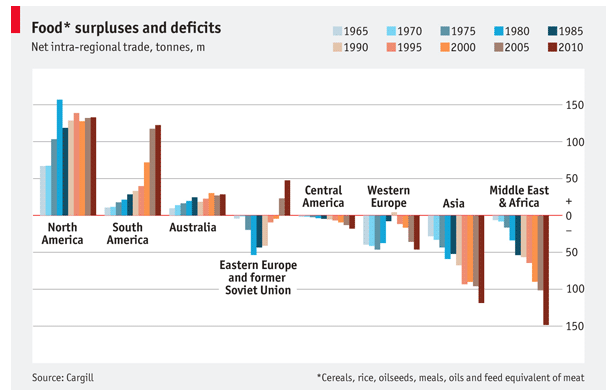

Note (6/15/16): This post proved prescient, as an article has just come out making more explicit the link between greater global economic connectivity in the last several decades and greater systemic vulnerability to climate extremes (in this case, heat stress). With the amount of money at stake and the size of the uncertainties involved, not to mention the natural counterbalancing that will occur as the benefits of free trade are defended, surely more such articles picking apart different aspects of this economic-climatologic intertwining are on the way. One of the many paradoxes of modern society is the seeming disconnect between the exponential increase in information and technological prowess on the one hand, and the decidedly slower increase in living standards, freedom, and social stability on the other. Move down a peg and there is another disconnect, between that slow methodical improvement of the world and people's pessimism about its direction — in almost every country the majority of poll respondents report they perceive the world as getting worse, in many cases by enormous margins. Both of these points were brought up very thoughtfully in a climate context in a January blog post by William Hooke, and I thought them so valuable that they were worth expanding upon here. As Hooke writes, modern society is built on margins — in finance, commerce, and even in love we are living with the knowledge that our competitors are very similar to us and it's that little bit extra that's enough to push us over the edge. Trade (of stocks and goods), just-in-time manufacturing, and online dating are just a few of the ways that efficiency is wrung, and advances are made, out of reducing the margin/processing cost to as small a value as possible. These advances are enabled by technology and global interconnectedness, but at the same time this system poses dangers for the exact reason that everything is linked together. Like dominoes that were once far apart but are now pushed close together, the elements of this system are worryingly interdependent, where the improvements in domino sturdiness (i.e. greater agricultural productivity, technological redundancy, gains in predictability of disasters) are offset by the fact that the consequences if they do fall are much more catastrophic and widespread. In other words, I argue that in many ways most people are no longer truly prepared for uncertainty because (despite our collective pessimism) we tend to conceive of large-scale disasters as a thing of the past. For instance, governments are no longer capable of, much less inclined to, stockpile food for the proverbial '7 years of famine', something only conspiracy cranks and fatalists are worried about. And this is not an issue unique to climate change — in a stationary climate they could also occur, though their probability would be somewhat lower considering that there have been observed increases in most kinds of extremes around the globe in recent years. Global production of commodities like food has risen exponentially over the past several generations, and in proportion we have lost a visceral fear of threats like imminent starvation; rather, people's pessimism seems to be based more on the grounds of a perceived risk of decreases in morality and leisure. Many countries have so-called rainy-day funds, but ironically in terms of physical necessities like water the trade-based global economic system has worked well enough (for those who can afford to purchase commodities at the going rate, anyway) for so long that an assumption seems to have set in that all the problems caused by 'small' idiosyncratic national-level sources of uncertainty — political, social, climatological — can be addressed with technology or trade, not giving much credence to potential systemic ones. These latter might take the form of simultaneous extreme heat or drought cutting yields in multiple of the world's breadbaskets at once, or disease racing through the genetically near-identical population of Cavendish banana trees, or a weak monsoon wreaking havoc on rice-growers in both India and China. We don't know exactly how likely such situations might be, only that they would be devastating and therefore should at least be thought about, if not actively insulated against. In some aspects of modern life, perhaps primarily those that are generally conceived of as risky, risks are calculated, contingencies are prepared for, and arguments are made as to whether preparations are sufficient. In others, like the environment, certain risks are also estimated as best we can with models, theory, etc. — but at the same time there is the "Titanic problem": that a wide array of climate risks can be well-estimated and prepared for in and of themselves, but, like the sealable compartments that the Titanic contained, the possibility that they may occur in devastating simultaneity is rarely accounted for. These caveats, of course, are properly read as a subtext to the recognition that global trade and margin-based economics have been essential to the productivity gains of the Industrial Revolution and thereby to the modern way of life. Indeed, it is almost because the system has worked so well (again, excepting those who were shut out of it for lack of funds or political access) that a certain level of complacency has developed. In a few short generations the popular mood can swing from existential fear of something to complacency, which can further veer over to rebellion, such as with the current anti-vaccination movement, spearheaded by people who surely do not recall the times when 21,000 Americans were paralyzed per year by polio. Shaking off this sense of complacency and narrow conception of climate- and weather-related risks, and adopting a global-scale perspective of them as befitting a global-scale society, is essential to properly and efficiently mobilizing resources to prepare for them. Marginal thinking has enabled the achievement of dazzling heights of productivity and inventiveness, and so in some ways has given us the tools to hasten its own demise — having the resources to liberate ourselves from the paradigm of thinking that it's the solution to all the world's problems.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed