|

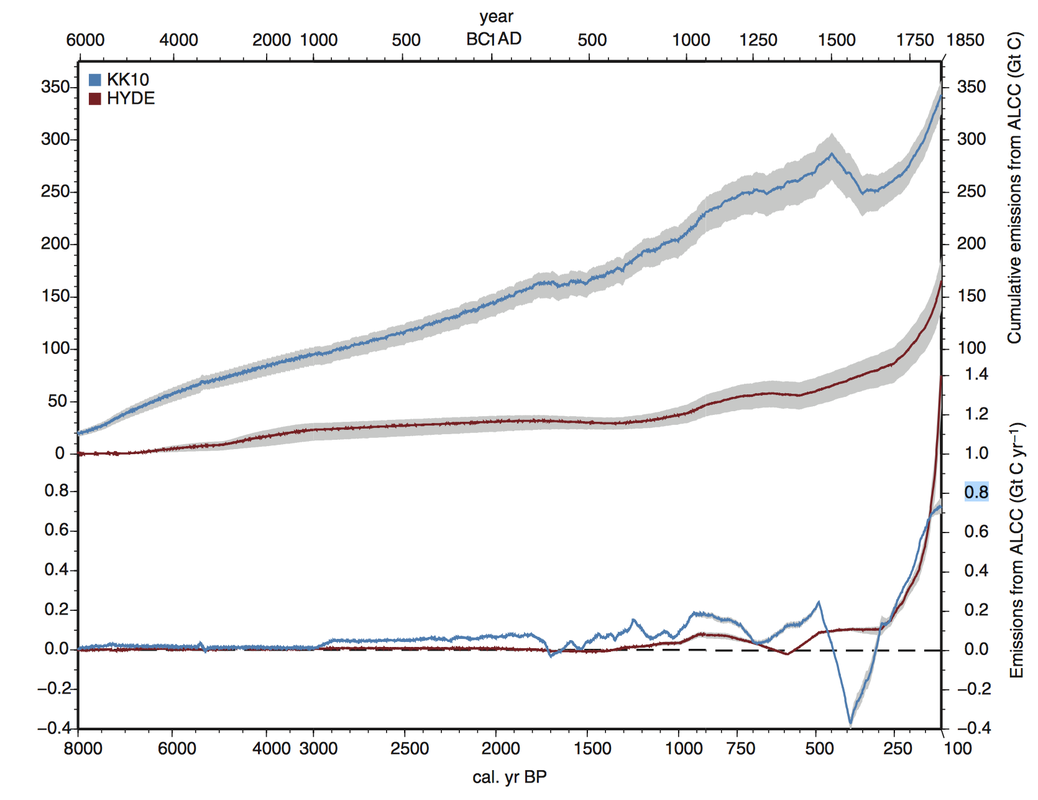

Ever since the discovery of the urban-heat-island effect back in the early 19th century, we've known that the geography of our settlements influences their climate. There are many examples, from very high temperatures to wind speed and precipitation. And it turns out that the effect of village- and agriculture-related decisions goes back even farther -- in fact, it's traceable back to about 1000 BCE (also see figure below). At the same time, in projects such as coastal redevelopment, Gulin New Town, and planning strategies for slums in the developing world, design and planning has the power to directly alter the physical contours of the world, and beyond that to inspire awareness and organic change of the intimate link between climate and human decisions. These kinds of efforts aim to envision neighborhoods that have less impact on the climate, both in terms of local heat-island-type effects, and in terms of their contributions to global greenhouse gases. For example, a project in the Netherlands proposed such ideas as coniferous trees along roadways to filter pollution and to block noise throughout the year, and (to build on a timeless Dutch practice) canals or other waterways that provide moisture for the vegetation, evaporative cooling for hot days, and recreation pathways for commuting and exercise. They term this suite of concepts -- applicable to new or existing development -- as "making a city climate-proof". While this is not strictly true, of course, this type of urban planning does fall under the category of "vulnerability reduction" and is gaining steam in the planning community.  Cumulative (top) and annual (bottom) anthropogenic carbon emissions from land use (primarily deforestation). The red and blue lines represent two different simulations. The invasion of the Americas and the subsequent precipitous drop in population and cultivated area there is seen as the sharp drop around 400 years ago in the blue simulation. Source: Kaplan et al. 2010. Ironically, multipurpose solutions (the Dutch canals mentioned above, or Masdar City in the UAE) are often a return to traditional ideas that gave way in the 19th and 20th centuries to modernistic approaches which frequently harnessed the technological optimism of the day to assert freedom from the tyranny of local natural conditions, in the form of standardized components and techniques. Arguably, this line of thinking can be seen in many facets of decision-making at the time, from the imposition of a street grid on natural topography to the belief that uniformity and predictability were desirable in every facet of life. Now that nature is less a thing to conquer and more a thing to preserve, the logic that resulted in our imposing our will on it is no longer there. The Earth is against the ropes, bruised and bloody, still standing but clearly hurting -- it would be heartless indeed to continue pummeling it. While the Earth is a big place by any measure, the collective decisions of nearly 7.5 billion people are more than enough to affect its course. No place is remote enough to be safe from our influence, for better or worse. Lately the emphasis has been on the "worse" aspect but the "better" part should be remembered too -- even if that betterment is primarily about damage mitigation.

Essentially, it could be said that we eventually wised up to the notion that fighting nature was a waste of resources in comparison to trying to live in harmony with it. Depending on the identity of the actors, the motivation behind this shift can range from hardheadedness to idealism, but to a large degree urban planners have converged on a set of principles expounded in initiatives like China's sustainable-development program: enlarging and improving green spaces, minimizing distances traveled by nurturing neighborhoods with distinctive identities and full suites of services, expanding public transit, designing systems to run smoothly using renewable energy, and creating or overhauling buildings and infrastructure to use the least amount of water and energy possible. The hope is that such cities will set off a 'virtuous cycle' where they have less and less impact on the environment, and so will have less and less energy/water/land requirements, thus having an even smaller environmental impact. Combined with a population that is still growing but expected to level off within a few generations, there's reason for optimism about the peaceful co-existence of our species and the planet that nurtured us. While perhaps ultimately we can build extraterrestrial cities (no need to worry about the vagaries of climate if you can make your own instead!), the tribulations of Biosphere 2 -- the largest sealed-environment experiment thus far -- indicate focusing our efforts on the planet we already know and (sort of) understand will probably be more fruitful.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed