|

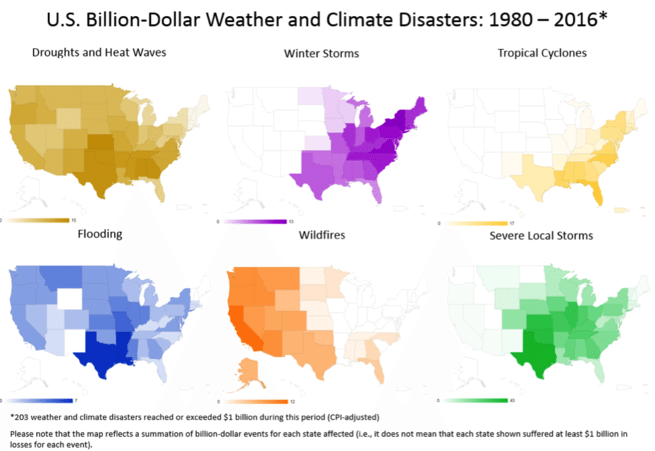

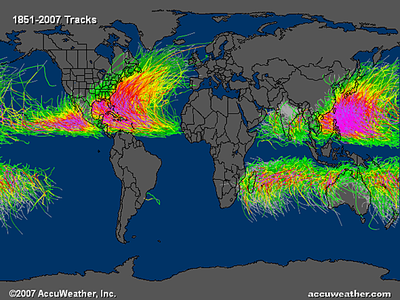

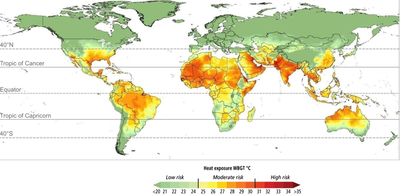

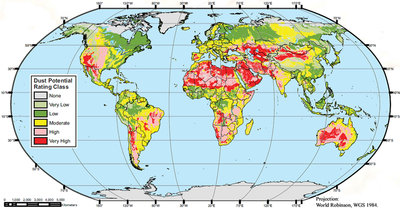

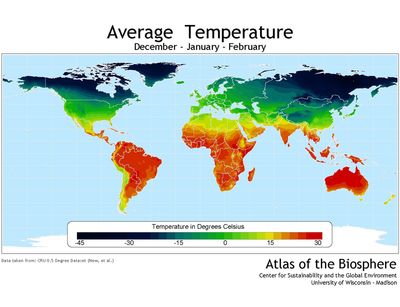

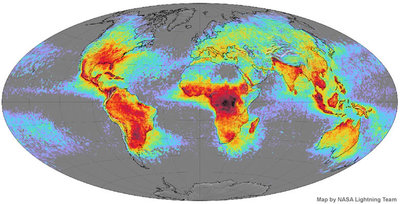

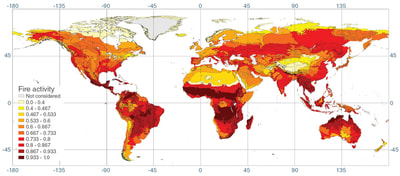

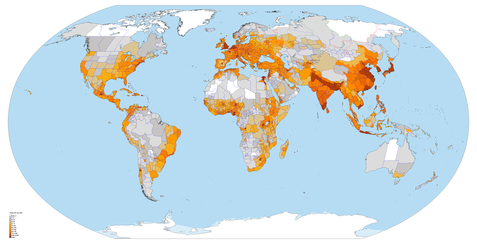

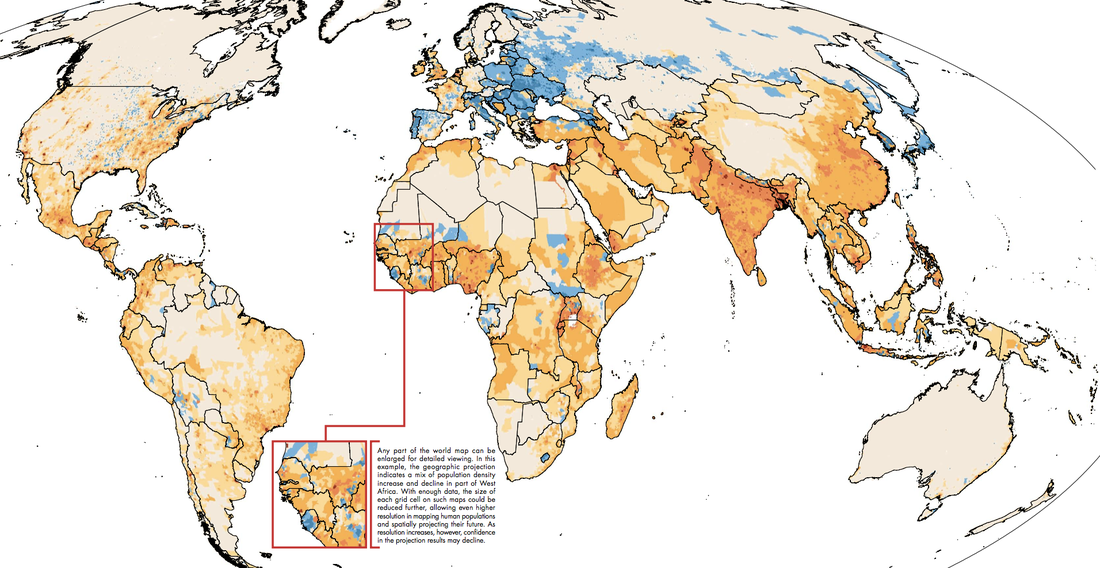

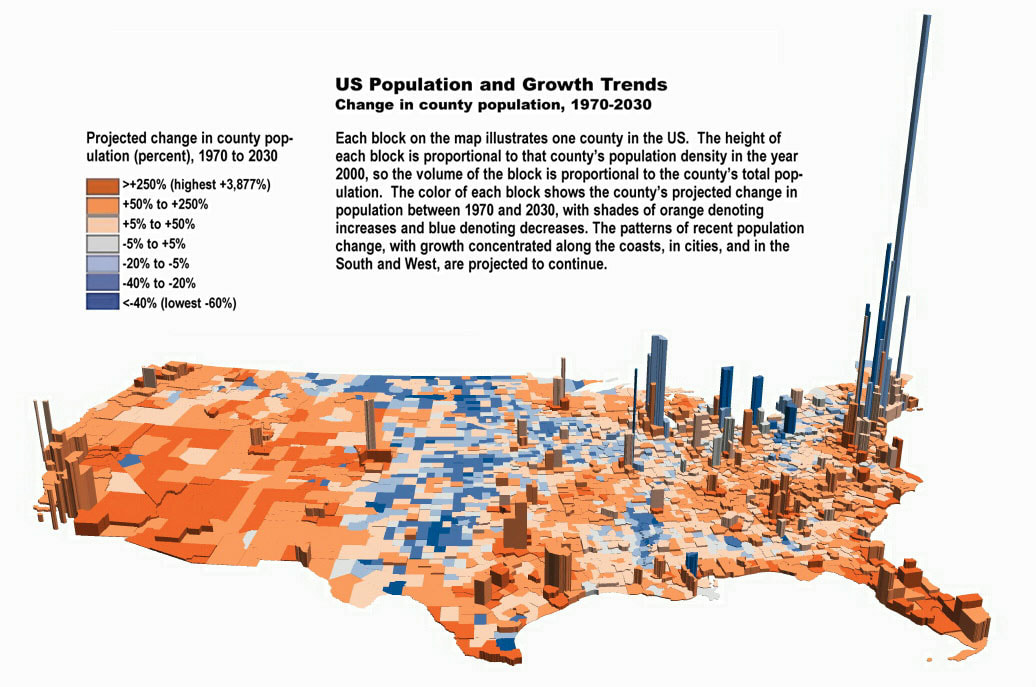

Two major features stand out with regards to recent population changes: the dramatic increase in the last 100 years, and the worldwide ongoing migration from rural to urban areas. Both of these demographic factors affect the ultimate climate impacts, just as much as any climate oscillation or long-term change itself would. In this post I'll focus on how current and projected interregional population shifts (due to migration and to natural population increase/decrease) amplify or curb human exposure to climatic hazards. A more-complete accounting of societal impacts would also consider non-population-dependent regional effects, such as those on agriculture, fisheries, or water resources. A pioneering study in this branch of demography quantified the surprisingly large percentage of the world population living in low-elevation areas vulnerable to future sea-level rise. Their main findings: the majority of megacities are on coasts, and the median person lives at an elevation of only 194 m. Thus the economic effects of even a modest amount of sea-level rise would be considerable, in addition to the disruptive migrations and political headaches. Estimates for these regional economic impacts (taking into account all aspects of climate change) indicate that the spatial and temporal benefits and costs will continuously vary, creating a complex mosaic of 'winners' and 'losers' as climatic averages and probabilities of extreme events shift simultaneously. For example, a simple review piece shows that cool temperate areas will gain comfortable mild days, while much of the tropics and subtropics will see formerly pleasant dry-season days become hotter and drier. Maps of other major extreme events are shown in the below image gallery; comparing these to global population density, and to global projected population change, provides a better sense of where future impacts will be most negative or positive, and what combinations of impacts will conspire to affect a given region differently than in the past. Above: Global maps of the climatological distribution of (clockwise from top left) tropical storms; extreme heat; dust storms; extreme cold (NH winter); thunderstorms; and wildfire. A detailed analysis of the intersection of population and climate change is well beyond the scope of this blog post. Some simple observational remarks: -Densely populated East and Southeast Asia are heavily exposed to tropical storms, extreme heat, and thunderstorms (leaving aside geological phenomena like earthquakes and volcanoes) -Rapidly growing northern India is exposed to extreme heat, dust storms, and thunderstorms. Not only that, but fertility rates are highest in precisely the most climate-vulnerable areas -While Eastern Europe and the US Great Plains are the loci of strong projected increases in extreme heat, the health effects (though not the agricultural ones) are mitigated by the population decreases in those areas -Accelerated urban warming will further compound cumulative exposure to extreme heat, as already observed in Chinese cities, among other locations Further study of specific regions and connections is warranted -- after all, it's the areas where the population is densest, or economic value highest, that are the most critical for supporting and protecting human society. The existence of many climate feedbacks of course strongly argues for the protection of sparsely populated areas like the Arctic and the Amazon basin, but to zeroth order, local problems have to be dealt with before remote ones. Avoiding a devastating heat wave or storm in India should, in my view, take precedence over preventing sea-ice loss on the grounds that it probably bears some connection with mid-latitude extreme events. Another way to frame this argument is that specific problems take precedence over non-specific ones (i.e. those whose exact form, location, and timing are not yet known). On decadal timescales, population projections like those in the above map are wrapped up with economic ones in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways dataset -- like the Representative Concentration Pathways projections for greenhouse gases, but for the more-nebulous human aspect of the future. This brings up another reason for periodic revisitation of studying the population-climate interface: it's always changing. The above map doesn't include (as it couldn't foresee) the exodus of people from Syria due to civil war, as reflected in this 2015 map of population change. Capital investment, too, is always moving around in search of profit; the economic impact of flooding in Thailand would have been much less than the actual $6 billion 20 years ago, before a surge in foreign investment and the country's incorporation into global supply chains. Anders Levermann makes the argument that adaptation to climate risk in this arena is much overdue. Finally, a nice map of the US sums up at a glance current populations and future growth. Comparing it with the types of extreme events experienced in each region is instructive as to where and what kinds of events we should expect more of in the future. For the last decade Texas has added the most people in absolute terms, but is also highly exposed to many of the most damaging weather extremes. Florida is beginning to see sea-level rise affect its valuable coastal properties, in addition to the habitual challenge of tropical storms. Of the six categories of events below, all are expected to remain constant or increase in frequency or severity in the generally more energetic atmosphere of the future. The longstanding trends toward population and economic consolidation on one hand make adaptation easier (as we have to protect smaller areas), but on the other make it harder (as we have more to lose if a concentrated area is heavily affected). Globally, nationally, and locally, policies will have the power to shape climate-relevant decision-making to some extent, but realistically advocating for preparation for the future is the main tool we have as scientists. Climate remains low on people's list of concerns, meaning that its effects -- pure effects as well as those tangled up with societal issues, e.g. 'climate justice' -- mainly flow from decisions made for other reasons. But this doesn't make plotting and understanding climate-related problems any less worthy of scientific study or any less valuable for our collective future.  Billion-dollar weather events for each US state for the 1980-2016 period, by primary categorization. In this methodology, if a state was affected by a given event, it is included in the count, even if its portion of the total damage was much less than $1 billion. Source: https://www.popsci.com/natural-hazard-risk#page-2

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed