|

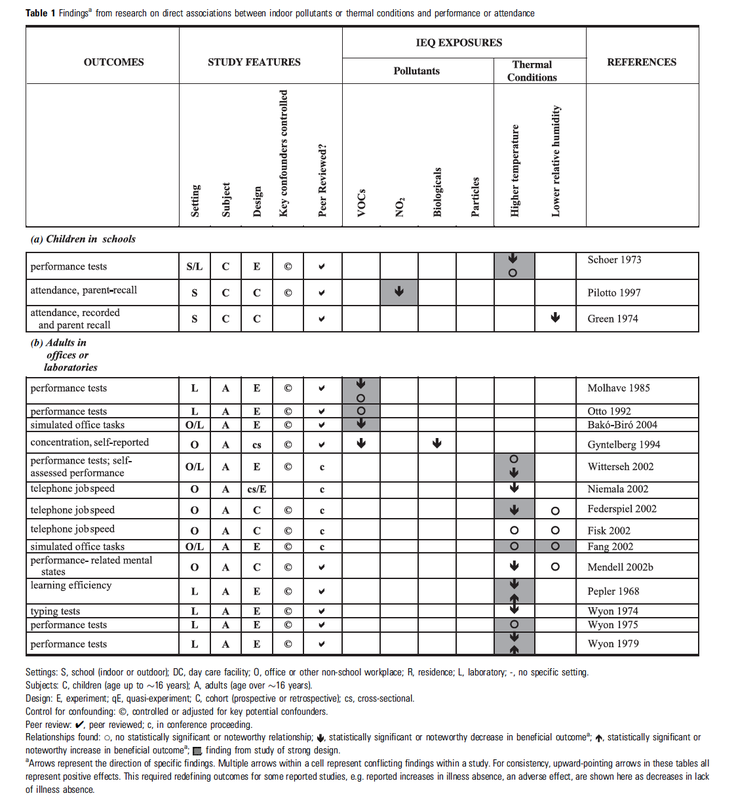

Current American political dissatisfaction with the 2015 Paris climate accord hinges on its perceived economic risks to the industries that powered the country's 20th-century explosion in productivity and living standards for much of the population. While futurists promise everyone will be better off when the transition to cleaner and more-efficient energy is complete, many still fear those promises are hollow -- leading to a society dominated by overlords of the finance-technology-energy complex -- and are based on a false premise of imminent global catastrophe. Harborers of these reservations naturally advocate for applying the brakes to investments in measuring, preparing for, and adapting to climate changes of any stripe, and consider such efforts a gigantic boondoggle. Independent of climate projections, geopolitics, and the subtleties of national moods, I thought it worthwhile to take a moment to assess the indisputable evidence at hand for the observed connection between temperature and various economic measures. In other words, to point out there while there is a real cost to doing something about a warming world, there is also a cost to doing nothing. The most-salient point is that there exists abundant evidence that high temperatures, like poverty, exact a kind of "cognitive tax" that seems to be an evolutionary adaptation to scarcity of a resource critical for survival. This temperature-productivity relationship has long been observed anecdotally, starting with Montesquieu in the 18th century (an "excess of heat" makes people "slothful and dispirited"). Quantitative studies have estimated that combating this heat with air conditioning results in increases in productivity from 5% (sedentary call-center work) to 25% (active kitchen work), and that the amount of outdoor labor -- from construction to gardening -- able to be performed during the hottest months could fall by half by the year 2200. Even in current conditions, outdoor laborers in Nicaragua opt to work about 20 fewer minutes per day (about 4%) when daily-maximum wet-bulb temperatures exceed the threshold of 26 C, according to public-policy graduate student Tim Foreman whom I spoke with at a recent conference. A listing of the results of some previous studies are shown in the figure below. Physiologically, these relationships are logical, given the body's reluctance to risk overheating itself and the decreasing effectiveness of our main cooling mechanism (sweat) at higher and higher temperatures. On an international scale, for poorer (primary-resource-dependent) countries, every 1 C temperature increase is associated with a decrease in economic growth of 1.3 percentage points. A different study found productivity peaks at an annual-average temperature of 13 C, irrespective of a country's wealth, though it is only at daily maximum temperatures above 30 C that the relationship becomes meaningful. Thus warming is expected to help contribute to raising economic growth in cool countries, while subtracting from growth in warm ones. This is even the case within the United States, but as with the country comparisons, the definitive reason for this relationship's persistence despite electricity, air conditioning, and the increasing prevalence of indoor work is still at large. Less expected, perhaps, is the link between temperature and mood, which is a nontrivial consideration on a personal level (e.g. in deciding where to accept a job or attend a school), but is rarely mentioned as it relates to society-wide impacts (e.g. with respect to possible changes in temperature or storminess in a particular region). I argue that this cost/benefit of climate change should be included in estimations of the overall effects. Leaving aside for a moment all other changes, the historical distribution of weather conditions sets a baseline for the culture of a region, month by month throughout the annual cycle, and this expectation may be considerably disrupted if monsoons, beach weather, snowstorms, etc. arrive at different times or not at all. It may be that this mood-weather relationship helps explain the observation that countries enduring clusters of repeated meteorological shocks are less able to recover on a unit basis than those for which the shocks are more evenly spaced out. And it's also likely a contributing factor to the expected erosion of economic gains in already-hot countries, which will face not only more-extreme heat but also more-severe storms. All in all, it's abundantly clear that we not only shape the climate to some extent, but that the climate also shapes us -- our productivity, our mood -- in subtle yet unrelenting ways. It's even the case that temperature affects things as intimate, individual, and seemingly intrinsic as condom usage (and resultant HIV transmission rates). And this is not to mention the myriad other effects on our health. All of which goes to show that, especially going forward, the very term 'natural disaster' must be re-evaluated as regards anthropogenically-influenced changes in temperature, pollutants, and storms. While there may be reasonable debate about the location and magnitude of these changes, and the cost of the interventions intended to address them, there should be no doubt that they affect us all, no matter who we are or what we do.  This rather complex table summarizes the results of many earlier studies investigating the effects of temperature and pollutants on the quality of work performed in sedentary indoor settings, with strong negative effects reported especially for volatile organic compounds [VOCs] and high temperatures. Source: Mendell and Heath, 2005.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed